I was pleased to have the chance to visit Trinity College, thanks to the invitation of Jason Jones. I was asked to talk about “Agency” which I something I’ve been writing about and around most of this year, I think. As usual this is my attempt to represent in writing what I said in the room.

****************************

Trinity College is located just west of the Kwinitekw River, within Wangunk homelands. The colonial city of Hartford occupies lands that were called Suckiaug, or black fertile earth in Algonquian. The river valley has sustained countless generations of Wangunk people, joined by indigenous communities from across the globe, including within Hartford’s Andean, Central American, and Caribbean communities. The land currently known as Connecticut is the territory of the Mohegan , Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett and Nipmuc Peoples,

I want to begin by telling the story of Bryan Short. You should read his own account of his experiences with submitting and FOI request for his data as collected by the learning management system (LMS) at the University of British Columbia. If you do nothing else, watch this video he produced on the collection of student data. Bryan was kind enough to talk to me earlier this year about what happened in his final year at UBC.

He was working at Digital Tattoo, which is a learning resource for students to teach about digital identity, and how what they do online might impact in the face to face world. He had a supervisor who encouraged him to look at the LMS, asking questions specifically about what data gets collected, and how it might be used

Bryan was funded through the center for teaching, learning and technology (the part of the university responsible for the LMS). He encountered people in the CLT who were encouraging a critical take, as well as people (in particular those managing the LMS directly) who clearly felt a bit defensive about his line of inquiry. He also recalls people in central IT services who, while worried about speaking out themselves, encouraged Bryan to be critical.

Bryan looked into the Terms of Use, and figured that the only way to learn comprehensively what was going on with his data was to submit an FOI request. And this turned out to be a big hassle because they his University didn’t actually have a process in place–suggesting to him that the expectation was that no student would actually ask about their data in the first place.

Bryan suggested that the lack of process, what seems to be a lack of caring about students and their data, was actually a lack of disclosure and transparency.

Over the course of trying to get his university to share what was happening with the data their systems were collecting on him, Bryan never felt comprehensively supported in his interrogation of the process. He encountered people who saw learning analytics as a way to help students. When “more forthright” instructors helped him ask questions by showing him the LMS dashboard that instructors could use for participation, he took that information to administrators, who were dismissive about whether the data collected would be actually be used (which does suggest we should be asking why collect data that is unlikely to be used…)

Bryan’s experience was that UBC was pushing back against his requests. They blew through a few deadlines, implying that his requests were unreasonable. Their pushing away of him made him angry, and motivated him to continue. He was invited to speak to grad students at the iSchool, and he encouraged people in the class to fill out the forms and ask for the data because he wanted to see if multiple requests would really break the university’s ability to comply.

As he spoke to me about this, he remembered feeling tenuous about the project. He even received emails from supporters that suggested that they were being pressured about what he was doing, and that he might get pulled into meetings about it.

At the end of his time at UBC, the university switched their LMS from Blackboard to Canvas. For his final online-only class, he chose not to agree to the terms of use for Canvas. That created tension between him and his instructors, who then had to email materials to him individually. He also couldn’t engage in class discussions with his classmates, and in the end of course this impacted his ability to be successful in classes, and he didn’t get same experience that others were getting.

Bryan filed another FOI for UBC and Instructure, and didn’t get information on time to do anything with it as a Digital Tattoo employee. The day he received the information was his last day at Digital Tattoo, and there could be no followup on his part.

Bryan remembers hearing instructors and administrators say that the data collected would “help us help you!” but when he asked for evidence that the data collection actually helped struggling students, there was nothing. There were, however, clear benefits for administrators wanting to manage and report on student activities.

So let’s think about this, and ask the question:

Who gets to say no?

I read and hear versions of “We have all this data we should do something with it” and “Help us help you” with no stories at all about students who were actually helped by massive data collection. When questioned, many suggest they want this data because they are coming from a place of care.

At Trinity, there is a merged unit–IT and Library, and as such is a unit in charge of multiple systems that collect and store student and faculty data,

And historically libraries didn’t keep all this data, because of concern about patron privacy and protection

The potential of the systems we have now to collect and surveill makes it easy to do market- imperative-driven things such as offer suggestions, create profiles, and there is plenty of pressure to do so.

How much agency gets surrendered to these systems, to the predictive algorithm?

Chris Gilliard (2016) and Safiya Noble’s (2018) works provide two important cautions about the ways in which digital structures reproduce and amplify inequality. Technology is not neutral, and the digital tools, platforms, and places with which we engage, online or off, are made by people, and informed by our societies, and all of the biases therein.

This, then is an important educational consideration: the tension between a “market forces” argument to use the data to predict and prescribe actions, vs. an approach that centers pedagogy, process, and potential, and resists prediction in favor of providing opportunities to see what might happen.

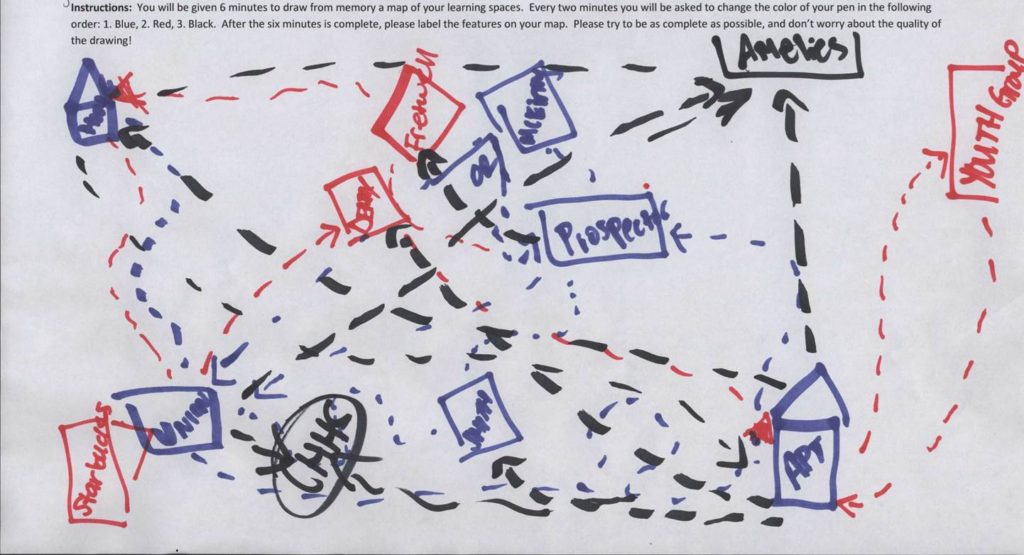

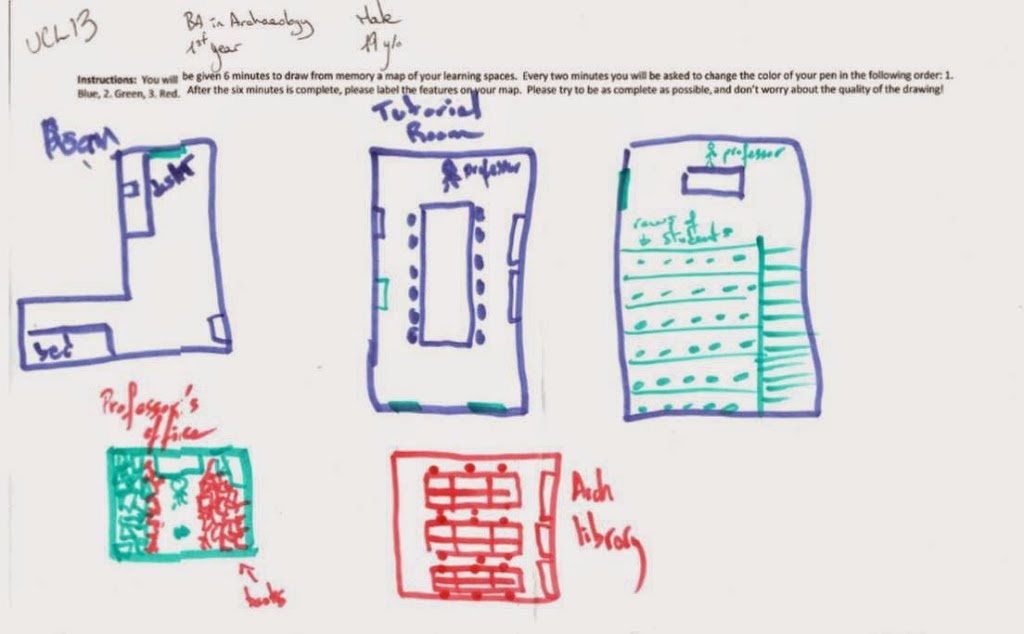

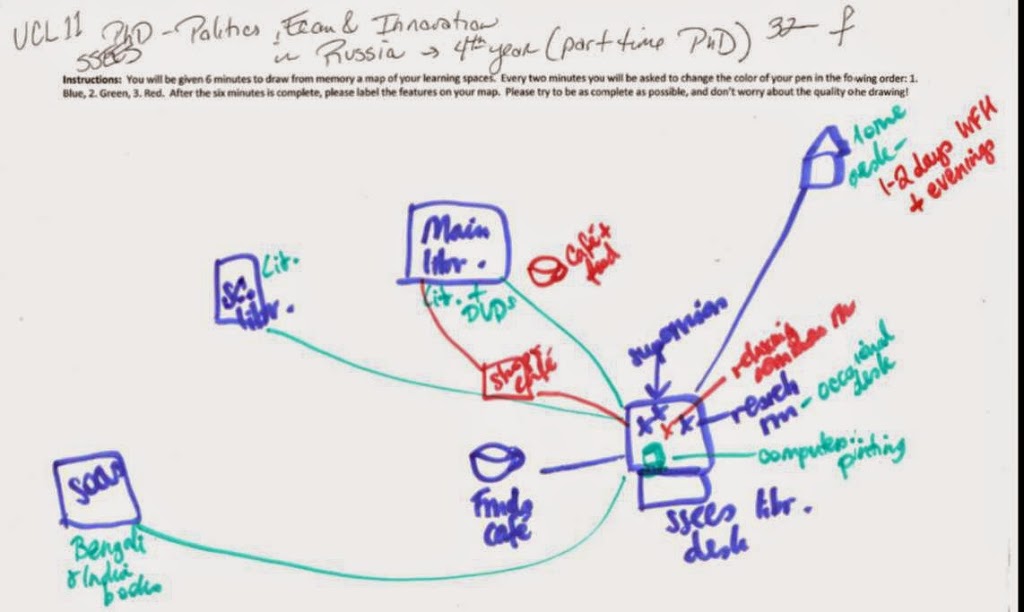

In my work as an anthropologist in libraries and universities I have contributed to physical space and web redesigns. There’s been an interesting tension between “find problems and fix them” and “explore how people study/do research/teach/write” I write about it with Andrew Asher in our article “Ethnographish.” In particular, we point to the culture of libraries (and the nature of institutions generally) as resistant to open-ended work that doesn’t have a concrete problem to solve:

“Libraries are notoriously risk averse. This default conservative approach is made worse by anxiety and defensiveness around the role of libraries and pressures to demonstrate value. Within this larger context, where the value of libraries is already under question, open-ended, exploratory ethnographic work can feel risky.“

Lanclos and Asher (2016)

I think these are related, the tensions I am identifying here. The contrast between treating students as problems to be solved (via predictive analytics) and treating students as people engaging in complex processes within education, emerges from a similar place that generates the contrast between “problem-solving” and open-ended exploration of behavior. These are different parts of the same conversation around “What is the role of education?”

“A college education, whether it is a night class in auto mechanics or a graduate degree in physics, has become an individual good. This is in contrast to the way we once thought of higher (or post-secondary) education as a collective good, one that benefits society when people have the opportunity to develop their highest abilities through formal learning.”

(Tressie McMillan Cottom, LowerEd 2017, p. 13)

Whether you think education is about people acquiring credentials (a commodity) or if it’s a collective good, important to society as a whole, will likely play a part in whether you think that people working in institutions should primarily problem-solve, or work in less transactional ways to gain insight.

In a lot of design work I see the use of Personas, and there are some interesting issues around the use of personas and the extent to which they do or do not get directly reflected in designs.

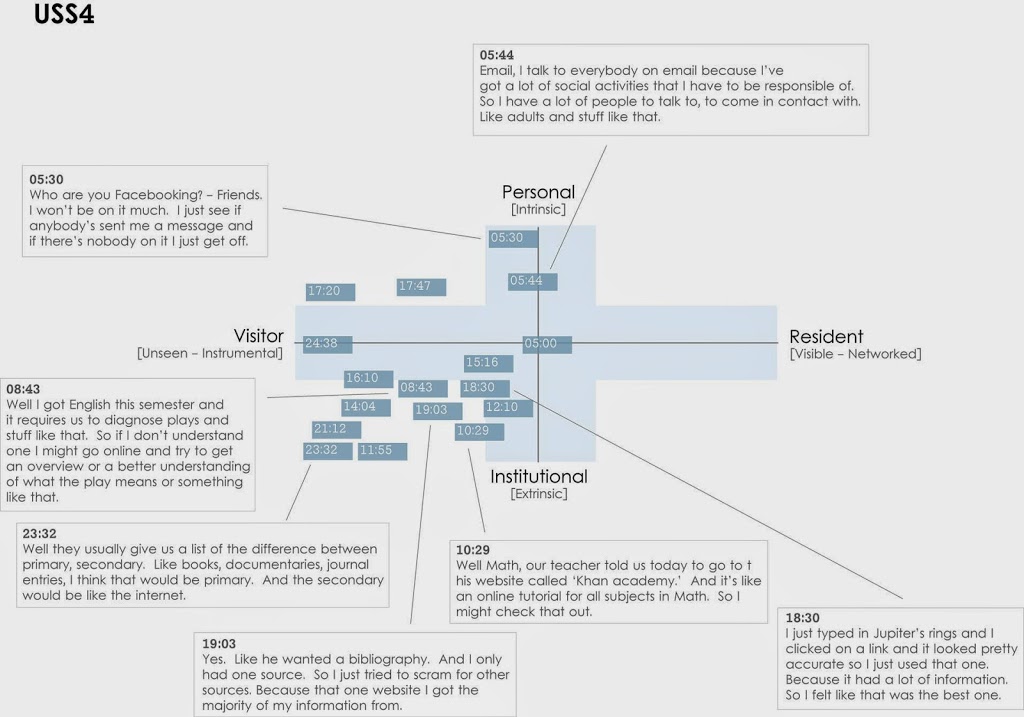

What I have also found in my own more recent work, as someone brought in to various higher and further education contexts to help people reflect on and develop their personal and professional practices, is that identity categories are quickly taken up by people.

We are primed in a variety of ways by diagnostic tests and also “fun” internet quizzes to label themselves. “I’m ENTJ” “I’m 40 but my social media age is 16” I’ve spent a lot of time in workshops trying to manage people’s anxieties around what they think these categories say about them as people. They apologise for their practice, because they can read the judgements embedded in the labels–”capable” “novice” “1st year” “1st gen”

We have people deciding that they were more or less capable depending on the label they felt fit them.

Early in my time doing work in libraries, I was tasked with some web usability testing. We generated tasklists, reported on the efficacy of web environments, etc. It was clear to me in the work that people didn’t sit down to a website and say “I’m a first year, and I’m using this website” They sat down and said “I’m writing a paper, I need to find sources.” So I was perplexed at the use of personas in web UX, because in the course of my research I saw people making meaning of their encounters with the web environment based on what they wanted and needed to do, first and foremost–not who they were. What I was told, when I asked, was that personas are useful to have in meetings where you need to prove that “users are people.”

(Sidenote–I’d rather start with “people” than “users” especially in a library context because your community includes people who aren’t necessarily visible “users” of any of your spaces)

When UX workers use personas, to frame our testing of websites, we have capitulated to a system that is already disassociated from people, and all their human complexity. The utility of personas is a symptom of the lack of control that libraries and librarians have over the systems they use. How absurd to have to make the argument that these websites and databases will be used by people. The insidious effect of persona-based arguments is to further limit what we think people are likely to do as particular categories. Are first year students going to do research? Do undergraduates need to know about interlibrary lending? Do members of academic staff need to know how to contact a librarians? Why or why not? If we had task-based organizing structures in our websites, it wouldn’t matter who was using them. It would matter far more what they are trying to do.

So I have a problem, clearly, with using personas as a design principle for organizing your spaces around identity

I think it’s important to consider: what are your systems and structures communicating to the people in your library about what is possible? Is it organized around who you think they are?

Or about what they can do?

One of those provides more room for choice and agency than the other

This is not to say that identity doesn’t matter–but what we want is for identity to come from, and inform how the students wants to work and what their work means. We should not want for identity to be a controlling category that limits what is possible.

Who is to say that undergraduates don’t need similar kinds of access to website space that faculty do? At some point both of them are writing, both of them are researching. The difference is in how deep a dive they do, not in the basic activities.

So, my advocacy would be for practice-based personas, if you are going to use them. Why?

Because it provides space for agency.

All year I have been giving talks that revolve around deCerteau’s distinction between kinds of agency, in particular tactical vs. strategic agency.

I have mentioned refusal and we can use deCerteau’s framing to distinguish between tactical refusal, which comes from from a position of no power, and strategic refusal, which can be engaged in by people with power.

Let’s think about our community members.–and here I will be indulging in a bit of personas

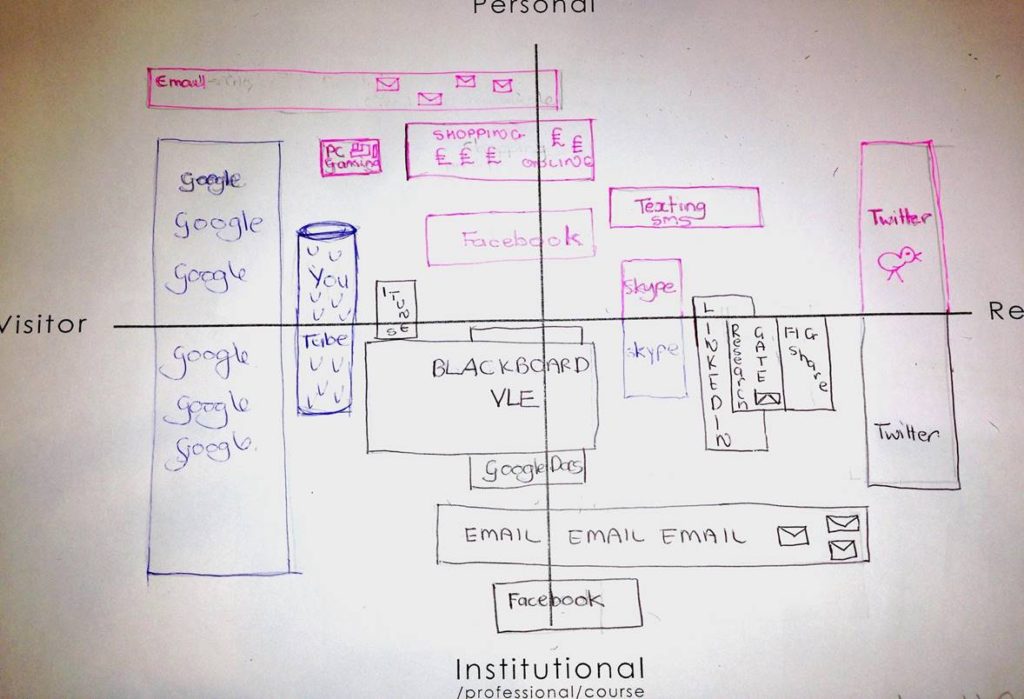

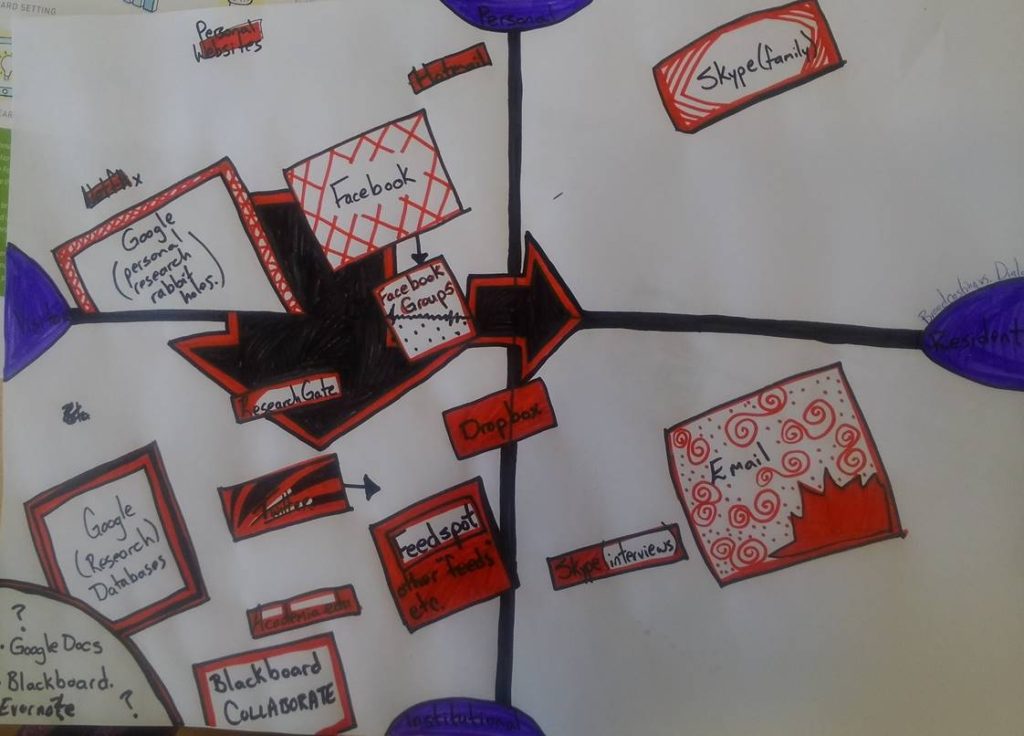

What does student agency look like? They can make choices. But there are often constraints around those choices. It’s worth asking, for example, in the case of learning analytics, the extent to which a student could actually choose not to participate in the systems that harvest data, and still successfully navigate to their degree.

Faculty have more institutional power than students, and sometimes more than non-faculty staff at universities and colleges, but they are themselves embedded in their own webs of power and influence, and don’t always get to be strategic. For example, they technically have choices about when and where to publish, but there are tenure and promotion requirements that constrain their choices. Even if faculty value Open Access and all it stands for, if they want tenure might have to submit their work to journals that are closed and paywalled, because that is what success looks like in their discipline.

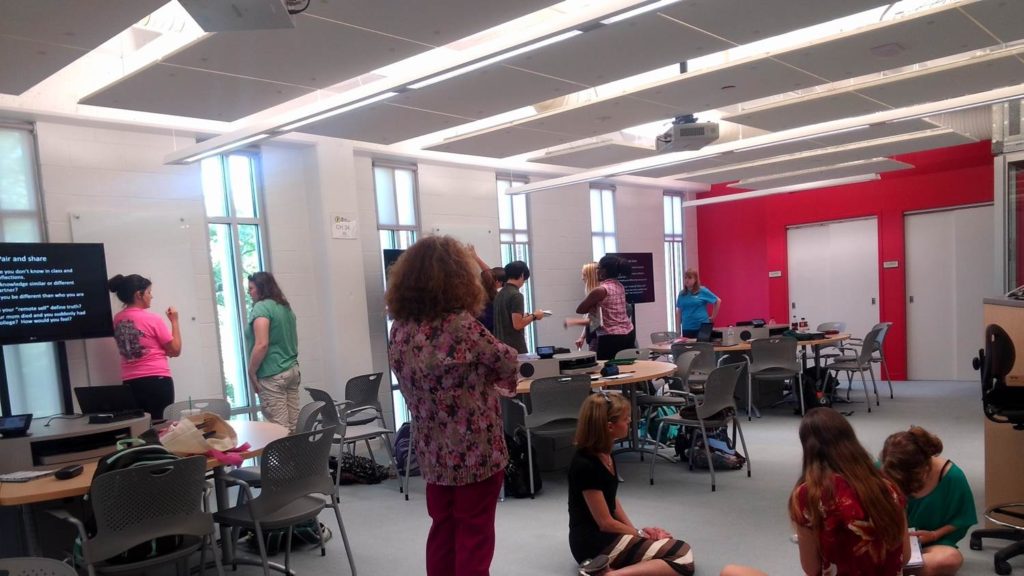

Faculty can also be limited in what and how they teach, as I witnessed when a junior faculty member at a university was discouraged from teaching in active learning classrooms because they “can’t teach as much content that way.” Regardless of that faculty member’s own perspective on teaching and effectiveness, they only had so much power to engage. It’s also worth remembering that any faculty member who is not a cisgendered heterosexual white man is even more vulnerable, and in need of care.

This is all about power and culture as well as practice.

So, what are people working in education, in IT and libraries, to do?

Let’s think again about orienting to practice, rather than identity. I find this useful not just as an anthropologist, but as someone concerned with social justice, and the ways that institutions can use identity to constrain and cap the potential that people have to do unexpected things.

Approaches to digital literacy can be similarly constraining–when we test people and put them in categories, that offers fewer options (and far less imagination) than assuming that everyone has a practice, but also everyone (faculty and students alike) upon arrival into an institution could use some information and help with How Things Are Done Here and What Is Possible.

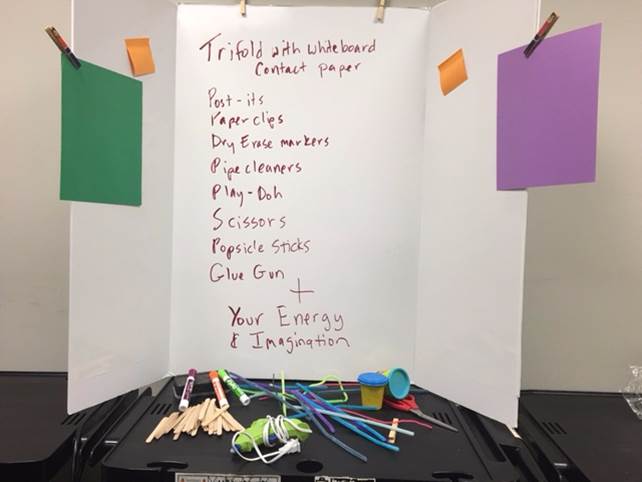

So in an ideal world, libraries and educational IT (and the universities and colleges in which they are embedded) would recognize the range of practices involved in scholarship (reading, writing, processing, communicating, researching, testing, etc) and then also have the resources to configure places (digital and physical) where these things are not only possible, but those possibilities are signaled to their community members.

This is not the same thing as “freshmen go here”

This is about flexibility, and communication, and also the ability to let go of what people “should” be doing when they do scholarship. While there are wrong ways to do it, there is also a spectrum of right ways, and much of that has to do with accommodating the ways that people need to fit being a scholar into the rest of their lives.

I want to point here to the work I got to do on the lives of commuter students. In that project, we interviewed student-parents about their academic practices, and where they studied (and why) to gain insight into their lives. We got to use this work to make an argument for a family-friendly study room in the library, and then evaluate the initial impact that room might have on the lives of students. This wasn’t a project that was reacting to a “demand” for it–there wasn’t a sense among students before we started this project that this was work the library could do. In connecting with students, and listening to the stories of trying to carve time out to study in the course of their complex lives, we worked towards giving our students more choices. This was the library Facilitating strategic agency : using the power that the library and education technology can have to create spaces for students to discover and engage in the kinds of practices that work well for them.

Open-ended ethnography can be a way to create space for us to imagine ways to allow agency in educational spaces. Exploratory work that isn’t just about “solving problems” can lead to insight, and allow library and IT workers agency too, to go beyond instrumental approaches, to move away from purely tactical, reactive approaches, and to gain access to more strategic levels of iterative planning and decision making

Resources and Further Reading

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. Lower ed: The troubling rise of for-profit colleges in the new economy. The New Press, 2017.

Chris Gilliard and Hugh Kulik “Digital Redlining, Access and Privacy” Privacy Blog, Common Sense Education, May 24, 2016, https://www.commonsense.org/education/privacy/blog/digital-redlining-access-privacy

Lanclos, Donna, and Andrew D. Asher. “‘Ethnographish’: The State of the Ethnography in Libraries.” Weave: Journal of Library User Experience 1.5 (2016). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/w/weave/12535642.0001.503?view=text;rgn=main

de Certeau, Michel, and Steven Rendall. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 2011.

Lanclos, Donna and Winterling, Rachael “Making Space in the Library for Student Parents” in Academic Libraries for Commuter Students: Research-Based Strategies, Mariana Regalado and Maura A. Smale, eds. (33-51). (Chicago: American Library Association) 2018. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-EwMBW4DXF1WUVrZEtYeUp0Y1BZbE5RTDBKakpzdWFqQ0Rn/view

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press, 2018.