I gave four talks in the span of two weeks this November, and this talk was the third one. I had the great pleasure of being invited by eCampusOntario to speak to the TESS conference, attended by a group of educators from across Ontario who teach and work in digital environments. It was my first time in Toronto, my first time with this particular group of people, and I was so glad I was invited.

The talk I proposed to give is the one that I will now try to represent as a blogpost. Some of this is chunks of other talks that I have given, but ultimately put together to make (I hope) a different set of points. It’s also pretty long.

I need to thank here not just the eCampusOntario folks for inviting me, but also Benjamin Doxtdator, who read and commented on earlier versions of this talk, and also Lawrie Phipps, who recommended me to the TESS organizing committee as a speaker. Thank you.

****************************

I am an anthropologist, and the machines I find myself within are multiple. The relevant ones today are the digital machines that create the online places in which (some of) education and scholarship take place, and also the machine of education itself, in which I have been a participant nearly my entire life, and which I currently make my field site as an anthropologist.

I spend a lot of time online, not just for work (alas?), and so I witness and participate in conversations, both as a part of my anthropological approach–“deep hanging out” borrowing from Geertz (1998)–and also just as one of the ways that I am in the world.

So when this story in the Atlantic came across my feed I engaged with it with a fair amount of anger.

I am tired of discussions of libraries and education that are zero sum games. In this article, the ignorance of practice in libraries leads the author to suggest that anything other than offering the “basics” is “fancy”

This is the false dichotomy of the traditional-looking past (and present) vs. the whiz-bang “innovative” future. And suggests that to serve students well, libraries need to choose one over the other–and furthermore, the article suggests that students do not think that libraries are choosing wisely.

My argument is that this framing is all wrong. You cannot have basics or innovation without fully funding education (including libraries).

Barbara Fister joined the conversation via one of her Library Babel Fish columns, in which she said: “Let’s give ourselves room to try new things while also maintaining things that have enduring value and stop thinking about it as a competitive zero-sum game.”

Kaetrena Davis Kendrick pointed out further

Kaetrena’s point about creativity, not innovation as it has been packaged and sold to us by vendors, is key here. How can educators have access to free range experimentation without creativity?

What we tend to see in education these days is a concern with “innovation” and so we need to talk about the relationship that it has with technology.

In April 2019 a report came out from the Department of Education in England. This government document set out a vision for the use of technology in education. And even though not all of us are in the UK, the approach this report takes is instructive for its emphasis on markets rather than educational practice.

That DfE report came out just after Lawrie Phipps and I had presented on findings from work we had carried out in 2018-19, on the teaching practices of lecturers in HE and FE. We released this report at Jisc’s Digifest in March, the same month that our article on this same work was published in the Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning. The report and the article describe and discuss the results of our in-depth qualitative research project

The research that Lawrie and I did seems to me the antithesis of that DfE report. While that report started with technology, and assumed that there wasn’t enough of it, Our assumptions were:

- People who teach have practices that involve digital.

- People have expertise, and make reasoned decisions around what to do and not do.

In our approach to this project we did not start off asking about technology (even though our research questions definitely were about technology in teaching and learning contexts). We started off asking about teaching.

And in talking about teaching practices, we learned a lot about the contexts in which people are engaged in teaching. And the nature of support.

“The opportunities in which innovation can happen are largely invisible to staff who are struggling with institutionally provided technology and teaching environments that are barriers to their teaching.” L. Phipps & D. Lanclos (2018) p. 81

In institutional contexts where people do not have the time, organizational support, or access to resources that would allow for exploration around new tech, or using old tech in new ways, it’s not hard to see why “innovation” is hard to come by. And also easy to see that “more tech” or “use the tech more” or even “create a market more friendly to vendors” isn’t going to produce more creativity. Or, more effective teaching and learning contexts.

In asking about teaching, we also learned a great deal about the networks, about the relationships in which people learn about and develop their teaching practices.

“We also wish to draw attention to the discussion of how important and occasionally fugitive networks are in developing, maintaining, and growing teaching practices. It is striking how difficult networks are to build and maintain without institutional support for the time and other resources such networking requires. Even as the UK has a number of national frameworks and organizations dedicated to HE and FE teaching, there remains an uneven sense of access to such structures, and the development that they might offer to people teaching in the sector. The distance between the networks people wish they had and the extra-institutional structures available for development of teachng is something that needs attention. “ L. Phipps & D. Lanclos (2018) p. 83

This speaks to the importance of networks for impact, and also the importance of digital in maintaining networks, especially for people who are far away from the “center” (and all the problems that the center-periphery setup hold)

In the UK, London sucks the energy out of the rest of the country, and educators outside of London often struggle to see and be seen by peers, and to learn from them (and to teach them about their own practice). This is not unique, and I’m willing to bet that’s also the case with Greater Toronto Area in relation to Ontario, or even within Toronto, as there will be pockets in any big city that are better resourced and more visible within networks than others.

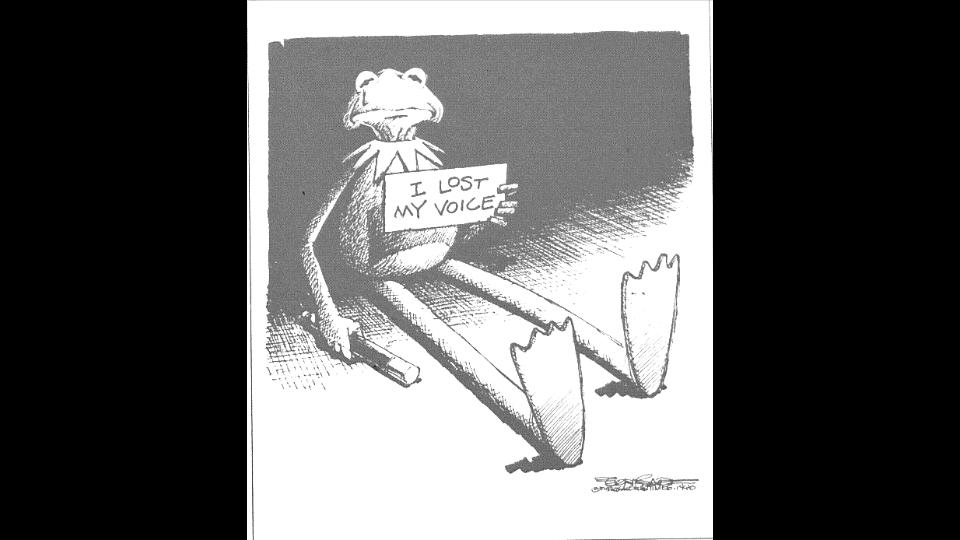

The notion of “hinterlands” is a colonial one, and certainly one that bears scrutiny and breakdown. Anyone’s center is relative to where they are. So, part of what digital connection can do is provide a chance to de-center the place with the most gravity in terms of funding, and power, and boost the voices and practices of folks who would otherwise have to struggle to be seen and heard.

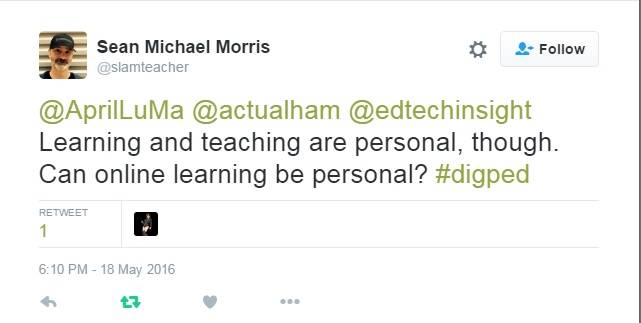

For example, I look to practices on Twitter that de-centering historic power structures (doesn’t make them go away, just gives another channel for building outside of pre-existing hierarchies)–a way to find and make an impact that hasn’t historically been available to everyone. I have been on Twitter since 2011, and still see a big chunk of it as a conference that you can actually go to without airfare, hotels, travel. It is, for all of its problems as a commercial platform, also a digital place that can enable the connections that people can make to each other.

In my work in libraries and education technology I am and always have been an anthropologist–and that comes with its own intense colonizing baggage, and a responsibility on my part to be better than my discipline has historically been

For example, the Nuer’s encounter with anthropology was one in which the colonial government was learning about them to try to control them After his initial fieldwork among the Azande in the Sudan, EE Evans Pritchard was hired by the Anglo-Egyptian government because of their conflict with the Nuer in 1920s. Colonial governors thought if they had more information about the people they wanted to control, they would be able to do so more effectively, so they brought in Evans-Pritchard to do anthropological work. Their desire for control was not met, but they tried, and with the help of anthropologists.

Franz Boas took up anthropology as his life’s work after his previous academic life as a physicist, who wrote a dissertation on the color of seawater. He is known as the Father of American Anthropology, and a champion of anti-scientific racism. In the late 19th and early 20th century–the “extinction narrative” had already quite caught hold, and Indigenous people in North America were the object of study at least in part because they were framed as “disappearing.” 19th century anthropology co-occurred with the systematic dispossession, persecution, and killing of indigenous peoples, the “salvage anthropology” that followed in the 20th century referred to “disappearing” people as if they were fading, not being colonized and displaced by white settlers. This is what Eve Tuck and Rubén A. Gaztambide-Fernández call “replacement”–the systematic and violent substituting of white settler people for Indigenous people. Anthropology is complicit in this process, freezing people in a particular ethnographic present, facilitating their erasure from any future, and their invisibility in the present.

In the mid-20th century, during the second World War, anthropological knowledge was leveraged as a way to better understand and so (it was presumed) control the US’s conquered enemies, the Japanese. Ruth Benedict did “armchair anthropology” during WWII, and her resulting work informed the occupation strategies by the US of Japan after the war. Benedict’s anthropological work was complicit in the military mission of controlling occupied Japan.

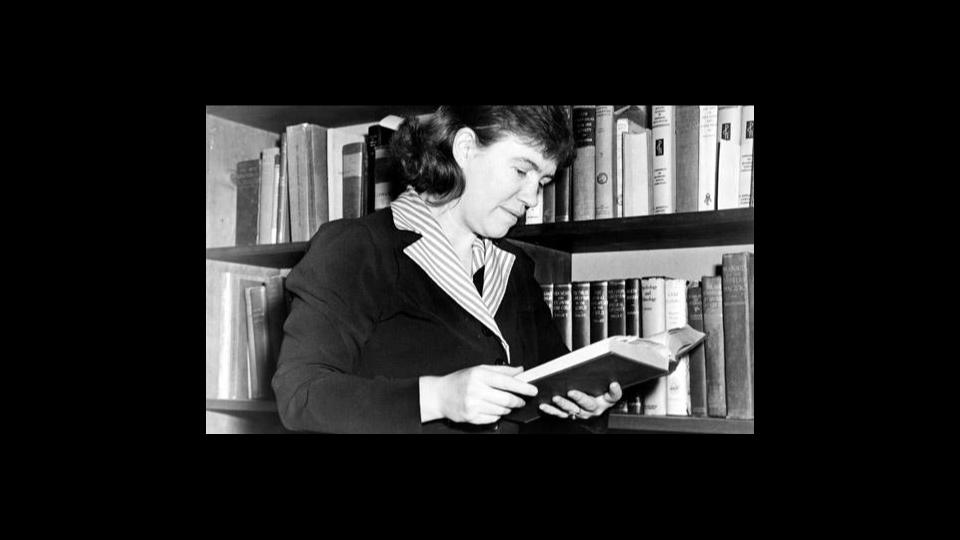

I turn in many of my talks and presentations to Margaret Mead. There are problems with whose stories she told, and for what purpose, and I do not want to leave those out of her legacy. In this context, I also want to point to the way her anthropological purposes shifted from those of institutional control to one of understanding, and it is for this that I value her work, in Samoa and also in Papua New Guinea.

Her intentions, and she was a student of Benedict, were to make the unfamiliar familiar. And also, to make the familiar unfamiliar, to question the practices of her own culture (especially with regard to sexuality, adolescence, and childrearing). She brought what she learned from other cultures back to her own, as a way of advocating for change. She used other cultural practices to feed her imagination, for what else might be possible. This is Anthropology as a (potentially) transformative project

Why am I telling you this? Many of you probably know the colonial history of anthropology.

I am telling this story of the different agendas of anthropologists because as an anthropologist, I take the mission of critique and change to heart. For all of her flaws, Margaret Mead wanted to use her disciplinary practices to understand and transform her own culture, and change it–not to transform the cultures of the people from whom she was learning, and also not to control them.

I do not want to facilitate erasure of people or practices, or to, with my work or my engagement with the work of educators, to suggest that I am “discovering” anything (as settler people have a terrible history of doing). I am concerned in my work with making practices visible, so that they can be recognized, and not always changed or “improved.”

I also want, via recognition of current practice and critique of institutions, to remind people that education, schools, and libraries are built things, are cultural artifacts, and are therefore not neutral. Participation in schools is also a colonial practice

One of the 94 calls to action in the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Report resulted in the recent launch of a digital monument to 2800 Indigenous children who died in the residential schools.

Schools have a deadly and damaging history for Indigenous people globally, and very specifically locally as well. This is the present, not the past, and we cannot build education futures without paying attention to the harms that settler education practices have done, and listen to people when they are (rightfully) skeptical of the place of schools in their lives and history. The legacy of colonialism means that white people in particular have a responsibility to listen to Indigenous and black people when they do not engage, or only engage with each other in places that do not include settler whites.

I am under the impression that attending TESS are people who facilitate and support the work of teaching and learning–librarians, education technologists, instructional designers–as well as teachers and professors of education. All of you, to my mind, are also students.

As people in the field of education, you (we) are often talked to about the “Future” of education. That “Future” is too often couched in language that betrays that the people speaking don’t know much about what’s going on in education. Sometimes, as we saw from the UK DfE report I mentioned earlier, they speak much more about markets than they do about education.

And I often see folks ostensibly concerned about the “Future” pointing to what they perceive as a deficit in digital capability, a lack of practice, to justify the change programs they are selling.

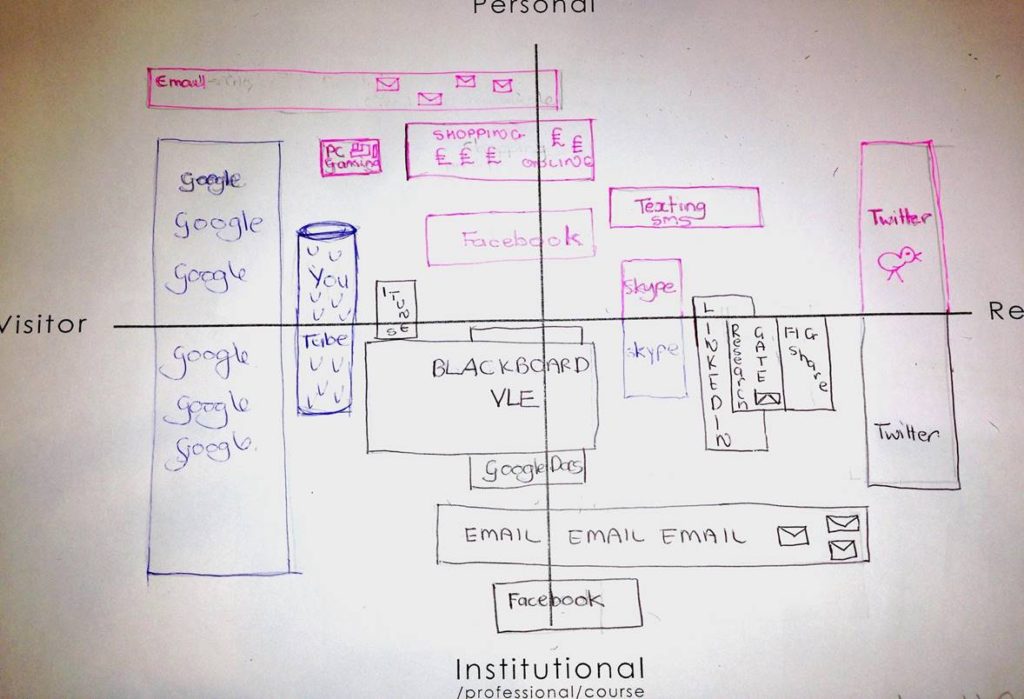

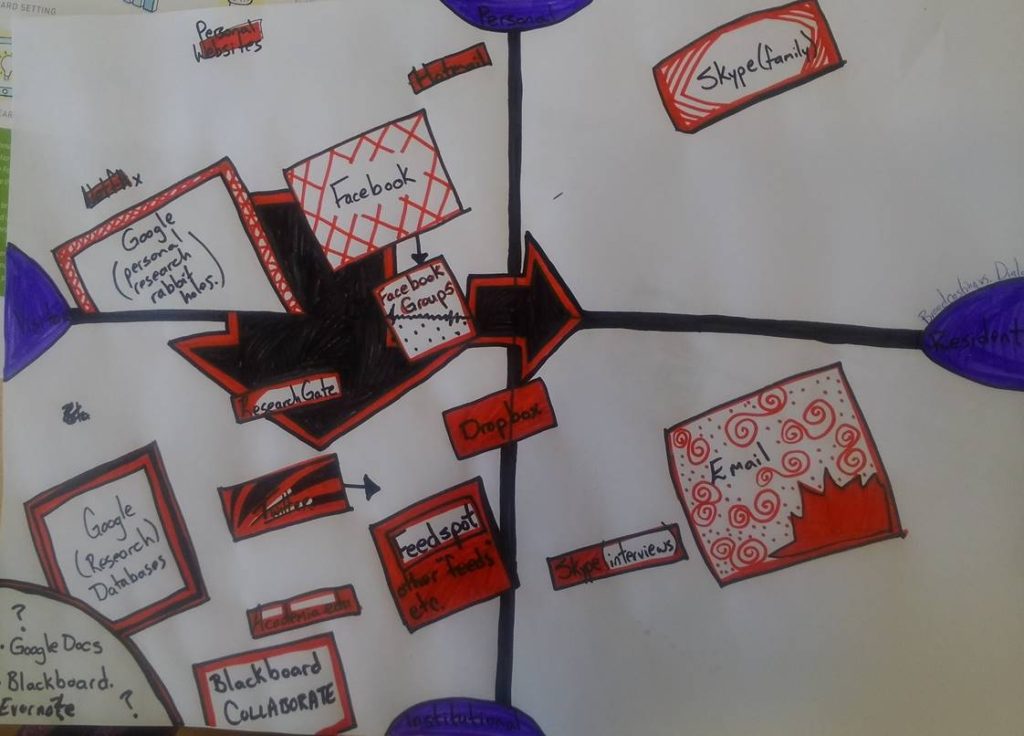

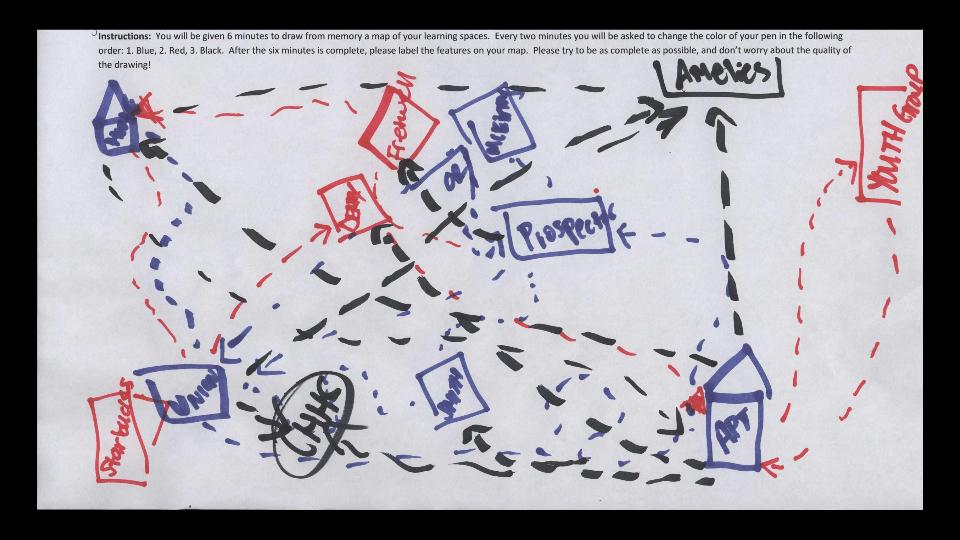

And, again, as an anthropologist, I find this interesting. Because I have been brought in as a consultant into situations where the powers that be assumed that the people working for them “didn’t do digital.” And then it turned out, once I ran the workshop, that there was plenty of digital practice, they just weren’t doing any of it in official channels at work because they did not feel valued, or safe.

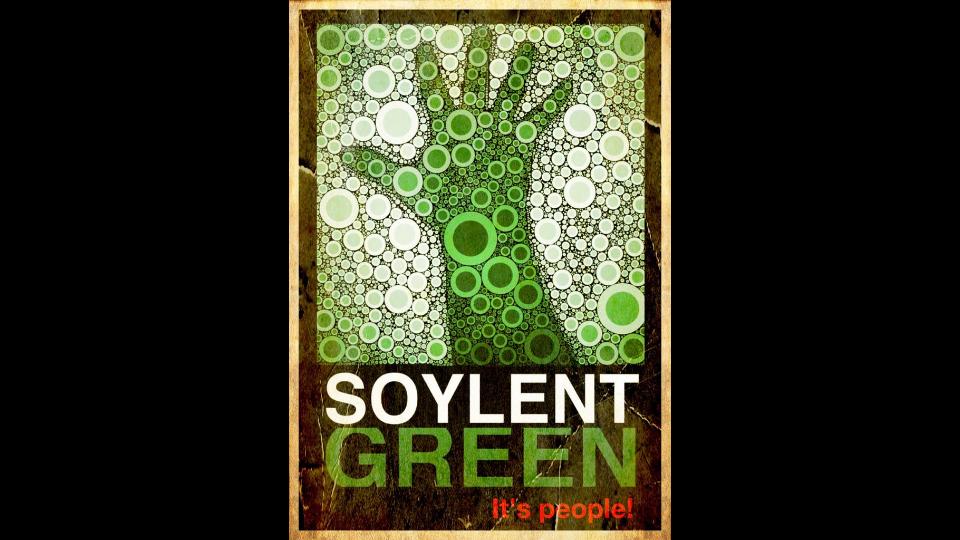

This assumption that there is no practice is what I have called a “Terra Nullius” approach. I don’t want to push this metaphor too far, because I don’t want to say that justifications for change initiatives are the same as the justification for colonization, dispossession, and genocide.

The terra nullius approach to digital (or any practice, really) takes away at least two things:

1) the ability to recognize and encourage good practices, and

2) the ability to recognize and change practices that do not currently serve anyone particularly well.

I know that the people attending TESS are already engaged in digital practices. It is the core of the work you do, if you are not yourself teaching online, you are supporting folks who are, and students who are learning online. So, already, no one gets to suggest that you have a deficit.

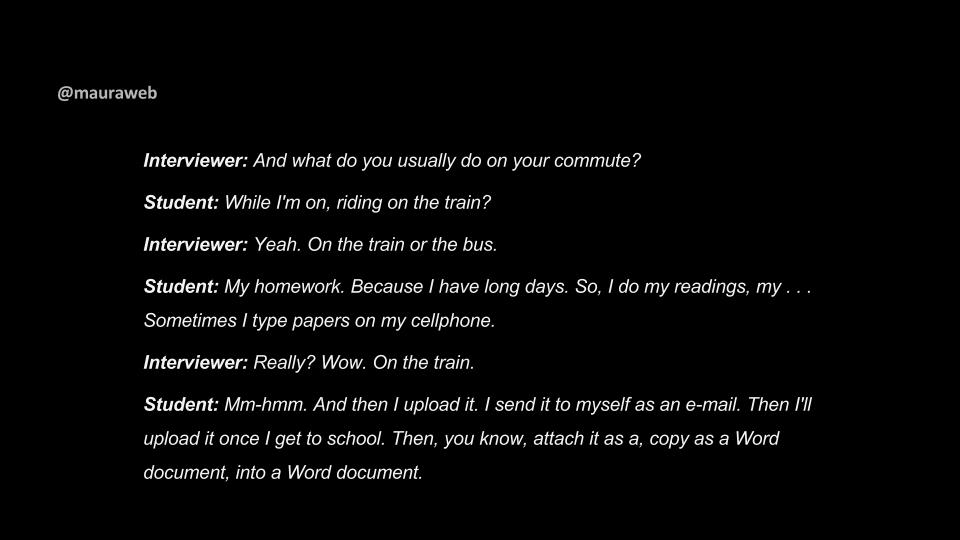

There are likely choices you make about what you do and don’t engage with. This is something I see in my own work, again not just with teachers but also with students These choices are not coming from a place of incapability, or ignorance, but from knowing what you do and don’t want to do.

Creativity cannot happen if people are having to fight the systems in which they work to do basic, baseline stuff, or if they are being punished for their informed choices by using systems that are in opposition to the ways they want to teach (for example: Turnitin)

Perceived lack of “innovation” isn’t about digital capability or incapability, but about systems that get in the way of practice. I agree with Kaetrena Davis Kendrick that we should be talking about creativity here

Current systems of inequality, of racism and colonization and sexism are also baked into current practice. So it’s not ever going to be enough to identify effective practice, but to ask questions about what is not effective, and why.

So, when thinking about practice, and fit, and transformation, and innovation, we need to think about for whom? And at whose expense?

I want us to work towards building a future grounded in present practice, informed by what should change as well as what is already effective.

Center and Periphery aren’t exclusively results of colonial practices, but they are characteristically so, What if we try to dispense with the notion of center as primary practice, and pay attention to the local wherever we find it? If we listen to the people in our respective communities, and be guided by them.

Eve Tuck and Rubén A. Gaztambide-Fernández write of “settler futurity” where the future is imagined much like the colonized past and present, which has replaced Indigenous people with settler whites, and requires all people to assimilate to structures and behaviors that center whiteness, what they call “the whitestream”.

An important antidote to the “whitestream” is the work of people who insist that they and their people are a part of the present, and will be in the future. I offer the example of Africanfuturist Nnedi Okorafor, insisting through her work in SF that African people will also be in the future.

With The Initiative for Indigenous Futures, Indigenous people are making and imagining their futures, not consigned to a past, or erased from the present. This is a refusal of settler futurity, an insistence that Indigenous people will create their own future with themselves in it. And supporting Indigenous and Black futurity will require of white people that they not-act, and not-speak, and occasionally not-know what is going on.

I want to again point to the history of Anthropology which has a goal of understanding practice, but does not always valuing those practices. Anthropology was traditionally about learning and gaining critical insight from the practices of “the other” but I would rather frame it as learning from “people who are not you, to try to move away from some of the essentializing problems around othering people.

Rather than “periphery” let’s say local–what are the local practices that emerge from the priorities of the communities in which you work that can guide and contextualize teaching and learning practices?

What can people who have been historically centered (white, settler, cishet) learn when they decenter their practices, step back and learn from the practices of people who are not them? And what happens when white people accept that they don’t always know what’s happening, and that’s OK? When met with refusal, that requires recognition and respect, not an insistence that historically marginalized, racialized, and colonized people “have to listen” or “should teach us.” We have to learn from people without insisting that they teach us. We have to do the work.

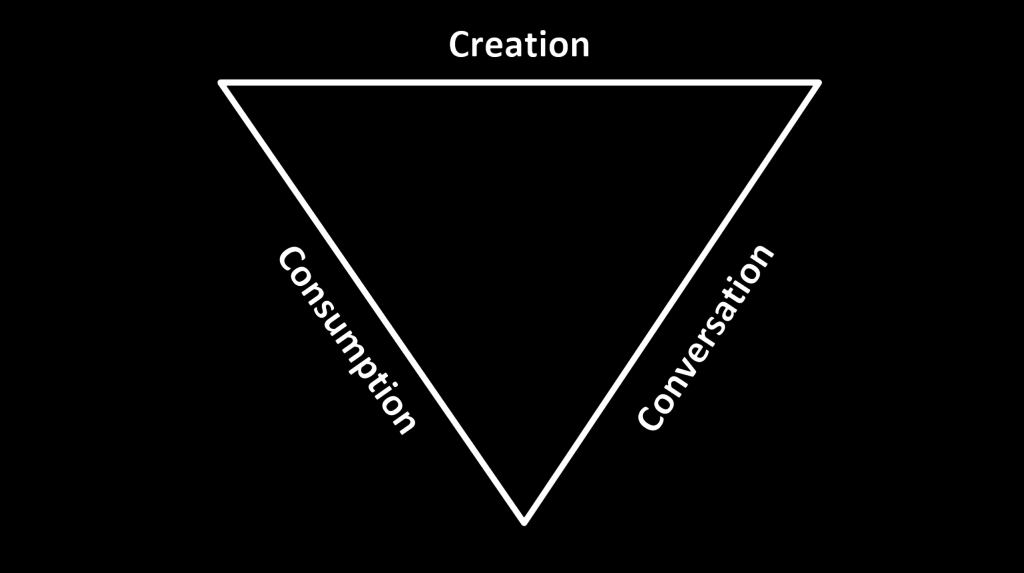

Digital gives access to networks of people who can share practice and make space for creativity

We do not need corporations for creativity. We need community. And support. Like we can find in places like TESS.

Who gets to experiment? Who decides what is impact? This is where critical consideration of power is key

In a time of austerity we must not choose basics instead of creativity. Our community deserves better

In times of austerity, people’s creativity ends up consumed with “making do”–this is not just “more with less” but the challenge of “the same with less.”

If you have the power to experiment, if you have the space to be creative and have it be recognized as truly extra, not just “making do,” how do you share that?

If you have the power to experiment, and have it be recognized as extra, who does not? Why is that? Are you white? Are you male? Who are you and what kind of privilege do you have? Who around you can you share your privilege with? Or, even better, for whom can you step aside, can you make room?

We need to advocate for centering historically marginalized voices and experiences.

(And here in the talk is where I chickened out, and under-prepared. I planned to point out that centering marginalized voices and experiences is the opposite of what the Toronto public library was doing by welcoming anti-trans speakers in their meeting rooms. I ended up not doing that, and I am sorry. I will try to do better next time, and prepare more fully to say all of the things.)

How can we support people to find their own answers? How can we encourage the centering of people who have historically been marginalized–Indigenous people, black and brown people– to make their concerns and practices the drivers of change and maintenance in educational contexts?

We need praxis–practice in a context of critical reflection and analysis. We also need collective action. No single individual working alone can effect lasting and constructive change.

With praxis and collective action, then we have a solid foundation for a future that learns from the present. And a way to avoid being cogs in our respective machines.

I want to help create spaces for building the future that I want to see. Don’t wait around for someone to predict your future for you

The idea that we might simply be handed or sold a predetermined future is terrifying.

The future is co-created.

Co-creation happens in spaces like TESS, and online sharing spaces, where people find opportunities to connect and to learn, and create new work building from existing practice. These are the places and methods for embedding our practices in our human relationships. This is where we must build, together, the future of education.

Additional References and Resources

de jesus, nina. “Locating the Library in Institutional Oppression. In the Library with the Lead Pipe.” (2014). http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2014/locating-the-library-in-institutional-oppression/

Department for Education (2019). Realising the potential of technology in education: A strategy for education providers and the technology industry. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/791931/DfE-Education_Technology_Strategy.pdf

Geertz, Clifford. “Deep hanging out.” The New York review of books 45.16 (1998): 69-72.

Johnson, D. (1982). Evans-Pritchard, the Nuer, and the Sudan Political Service. African Affairs, 81(323), 231-246. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/721729

Lanclos, D., & Phipps, L. (2019). Trust, Innovation and Risk: a contextual inquiry into teaching practices and the implications for the use of technology. Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 4(1), 68 – 85. https://journal.ilta.ie/index.php/telji/article/view/53

Morris, S. M., and J. Stommel. “A Guide for Resisting EdTech: The Case Against Turnitin. Hybrid Pedagogy, 15.” (2017).

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

Tuck, Eve, and Rubén A. Gaztambide-Fernández. “Curriculum, replacement, and settler futurity.” Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 29.1 (2013).

Unsettling America (blog) https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/

White, David, and Donna Lanclos. “The resident Web and its impact on the academy.” Hybrid Pedagogy (2015).