Last year’s tote, this year’s badge.

UXLibs II, with hindsight, feels like it was always inevitable , but right after the exhaustion set in last year after UXLibs The First, there was no sense from anyone (outside perhaps of Matt Borg and Andy Priestner) that it was of course going to take place. We even thought that if it did happen, it might be in two years (and possibly in Moncton). I was really really pleased to find out that they were going to take the plunge, have a second event, and see what else could emerge from the UXLibs community this time. A different event, with some of the same people, and with some new people, and with more things to talk about and explore.

I was thrilled to be invited back to participate in any way. I love the UXLibs team, the community they are building. I want to hang onto the hope, drive, and positive energy they are bringing to our practices. So I’ll put these words here, and look forward to hearing when and where we all get to be together again for UXLibs III.

Last summer, Ned Potter tweeted this to me:

When Ned introduced me to the UXLibs II group this year, and said out loud what he tweeted last summer, I smiled and was grateful to be in such a friendly room.

There are those who measure their success as an anthropologist by whether or not they are kicked out of the place they do their fieldwork. I prefer to measure mine by whether or not I am invited back–I am so pleased to have been invited back.

I’d like to tell some stories. And then we can think together about what they might mean.

My mother’s back garden.

My parents live in Southern California, and they have been in this house since 1983. My grandfather, my mother’s father, grew flowers and fruit in his yard in Louisiana, where she grew up. I remember visiting him and eating satsuma and kumquats off of his trees, admiring his tulip tree, taller than his house, and eating the marigolds (well, when I was very small) from around the lamp post not far from the swing set. My family moved into the Southern California house when I was 13, to citrus trees, plum trees, one white nectarine tree (that fruit tasted like heaven) and a whole lot of other things my mother didn’t really like very much. Since then she has been planting, digging, replanting, and this is what we have to show for it.

These amaryllis came from my grandfather’s yard in Louisiana.

My mother’s gardening philosophy: plant what you think might work.

If it dies, there are two lessons to learn:

1) don’t plant that again

2) PLANT SOMETHING ELSE

Far too often, organizations just don’t plant anything else. There needs to be an additional step–the reason they tried something in the first place was that they knew something needed to be done. That situation hasn’t changed, even if the plant they tried is dead. Plant something else!

One hazard of being in organizations within Higher Education such as libraries is there are people who’ve been around for so long that they remember all of the plants that have died–some of them keep lists! And that list of dead plants can seem like reason enough to never plant anything new again.

An addendum from my mom: sometimes, the plants die and it is your fault. You didn’t water them enough, you put them in too much sun, or not enough. The things you do always take place within a larger context–provide yourself with enough space to reflect so that you have a fighting chance of figuring out why things didn’t work. And then still, try something else.

Ethnography can give people a window onto possibility, not just onto what has been done, or what people say they want, but what can be done, and how useful it would be. Having a sense of the larger context in which you try stuff is crucial–this is what I keep talking about in libraries, not existing in isolation, but in a network.

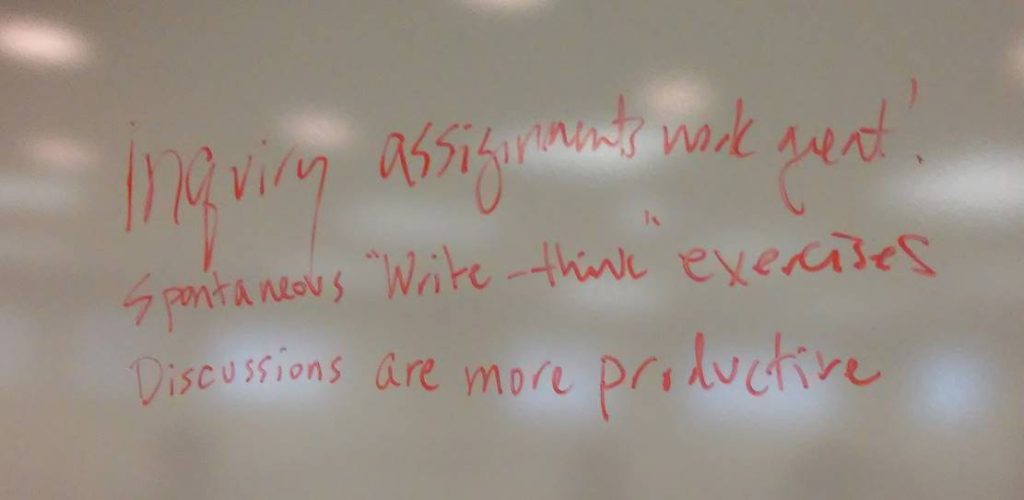

The tracks of UXLibs II are Nailed, Failed, and Derailed.

Here is where I am a bit cross with you, UXLibs darlings: I happen to know that there were far fewer Failed and Derailed submissions.

I think I might know why, I think it’s because of that word, fail, and even the sense that you got derailed, it’s hard to talk about that, it’s easier to talk about our successes, (that’s what I’m asked to talk about in my work, in my day job–what are we doing well?) It’s easy and satisfying to get to stand up and say “We did a thing! It’s great! Yay us!”

And we should have those opportunities. But I find conferences these days, especially library conferences, full of these kinds of self-congratulatory presentations. But failure and derailment have the power to reveal processes, structures, possibilities.

I’m so much more drawn to the Failed and Derailed parts of UXLibs II, because while it’s great to hear success stories–they are necessary beacons to our ambitions– it is to me more interesting and useful to hear the things that didn’t work out, or didn’t go quite as things planned.

For instance, my entire career, the whole string of reasons that I am here today, are because at a very important part of my life, I was utterly derailed.

To even get to the point where you fail, you have to have gotten the chance to try. So when your subjective experience of trying to effect change is not successful, what do you do?

What does “doing things” mean? What do we mean by “action?”

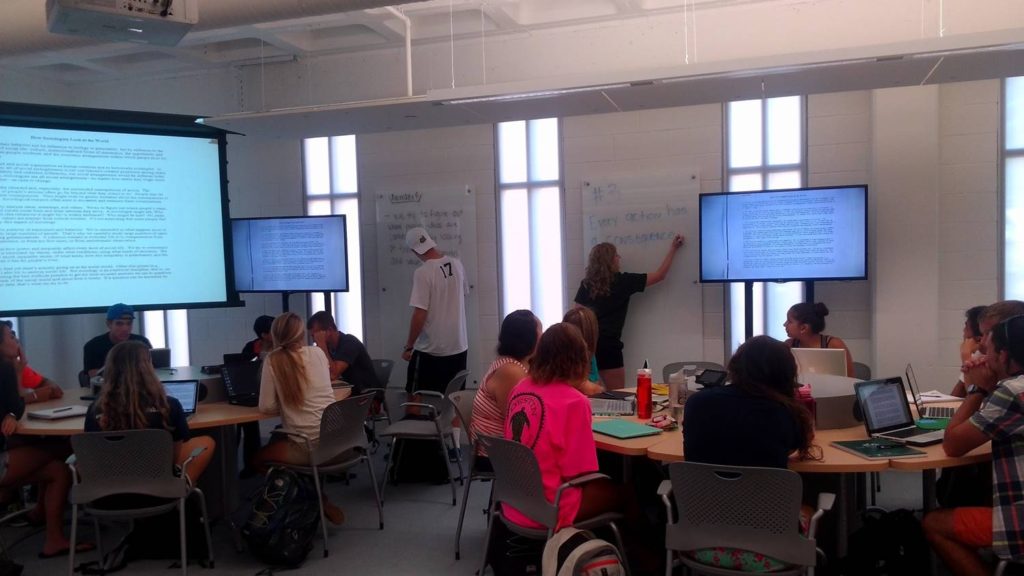

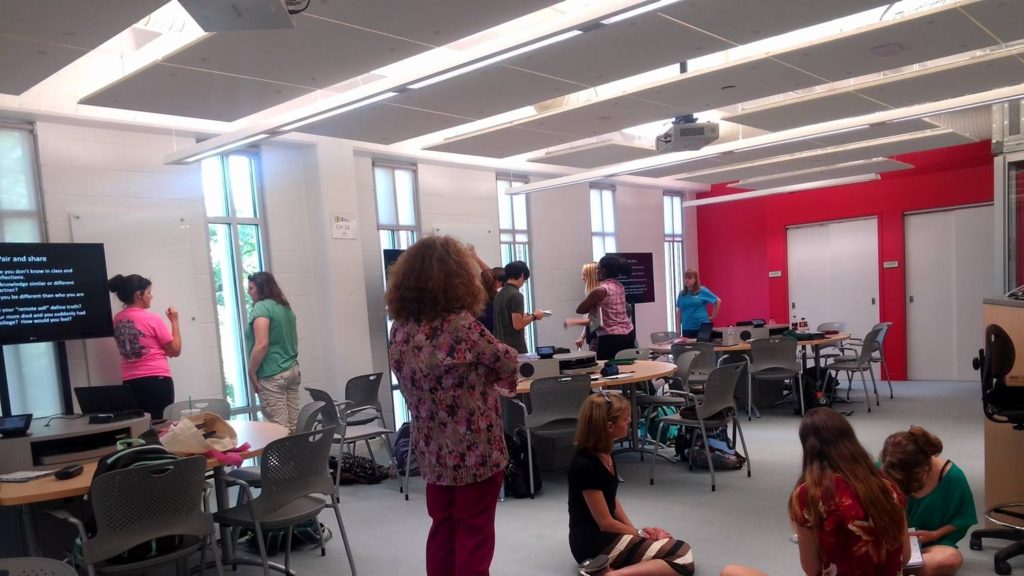

Portrait of the anthropologist in the field (far right, back turned).

Once upon a time I did fieldwork in Northern Ireland.

I was doing cross-community work, and working in schools because I wanted to collect children’s folklore, and being embedded in schools was a safe way (for the kids and for me) for me to be in touch with them and talk to them and observe what they were doing when not in the classroom. One school in particular was small, so small they did not have regular recess times, but just went out on the playgrounds when their teachers felt it worked with their schedule. I sat with those kids over school dinners to maximize my time with them.

One small boy in particular would tell me jokes;

“What do you call a man made out of cement?”

“A wee hard man.”

That punch line, which made my 8 year old friend laugh like a drain, was also real. This was a school that had a paramilitary mural painted on its side. The “hard men” were these kids’ fathers, uncles, brothers, cousins, grandfathers.

So there was a time when there were very few kids at school that day, for several days, and the reason that the kids were absent was because of a feud. Not sectarian violence–that’s Protestant-Catholic. Just violence. Kids whose family members were involved in Loyalist paramilitary groups were staying away from town, everyone was hunkered down at home.

And I felt more useless than I had in my entire life (Note: I’ve since felt more useless than that, but not by much).

So I took my feelings to the pub, to my friend Noel–a former social worker. And he shared that the same feeling of uselessness had dogged him while doing social work. And had in fact informed his move into doing an anthropology degree. So he re-framed things for me. While I had the sense that I “wasn’t doing anything,” my friend suggested rather that anthropology is not just doing something, but providing a platform from which to effect more change than direct action sometimes yields. You can’t fix things. But that doesn’t mean you’re not doing anything.

People who work in libraries want to FIX THINGS. I see this, they want to find problems to solve, and solve them.

But there are other things to be done once you gather this kind of information, the insights yielded by ethnography. You can report, observe more, collaborate–there are so many different ways of approaching results, and not all of them involve coming up with a Fix for a Problem. I wonder how we can effectively move away from that sort of solutionism.

Ethnography is not just about identifying problems to solve. It’s about gathering different understandings. We need to be up front about how qualitative approaches fundamentally change the ways we approach Doing Libraries. Centering our practice around qualitative data and analysis flies in the face not just of LIS, which is still deeply embedded in the quantitative, but also current entrenched practices in Higher Education.

This shift, it’s bigger than Libraries. Libraries exist (as I have said before) in a larger context.

So it’s important to have a sense of what qualitative approaches such as ethnographic methods and perspectives can do in terms of informing new approaches and developing new practices.

I’d like you to think about the rooms you’ve been in where they talk statistics, talk about all the things they don’t know, and cannot know from the numbers. THERE ARE THESE OTHER WAYS OF KNOWING THINGS, they can help us get at the “whys” to figure out, that numbers cannot show.

I recall a poster session at ACRL, where there was a librarian who had carried out a qualitative (interview-based) study, and had results, but was uncomfortable with her study’s “low N” and so she made meaningless bar charts to put on her poster. She told me this made her feel better about talking about qualitative results that she didn’t trust. I see this so much, people being unsure about this unfamiliar approach and running back into the warm embrace of their bar charts and figures.

How do we get leadership to trust qualitative approaches?

How do we get our colleagues to trust us, as qualitative practitioners?

Your Methodology will not save you from the Culture of Libraries.

This project, here within UXLibs, is not just about telling people how to do this work. It’s about getting people clear about why you would do this sort of thing in the first place.

This a core problem: how do libraries, how do people in higher and further education make the argument for using these techniques instead of quantitative ones? Or just as much as? I’ve made arguments for mixed-methods libraries, but I think it’s actually more important to make an argument for qualitative libraries, because the default is still quantitative. “Data” is still often in terms of how much, how many, with credibility expressed in terms of quantity. “Let’s do a survey” feels safe. That feels like communicating effectively with the Powers that Be, and with our users and communities.

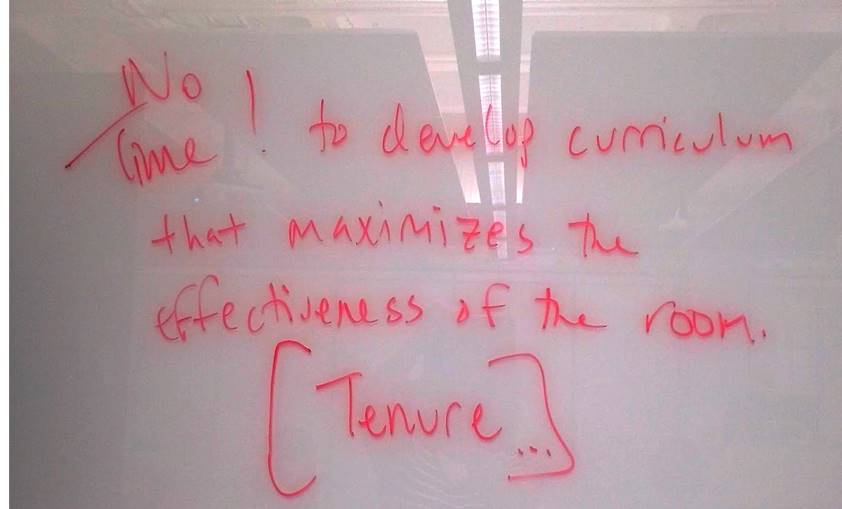

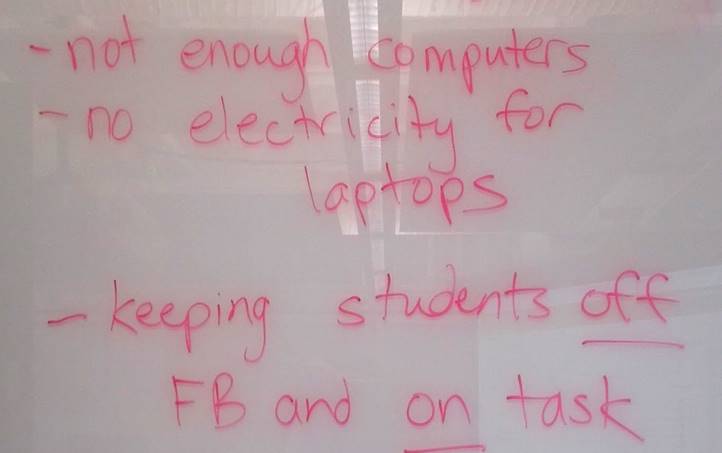

It’s important to be clear that when we are asking libraries and higher education to take qualitative methods and data seriously, it’s going to be challenging. Because it’s asking for:

–time

–resources

–risk-taking

–vulnerability

— and the de-centering of all-powerful quantitative data that SOUNDS SO AUTHORITATIVE.

It can feel like we are taking people’s numbers away from them when we insist that they should be talking to people about motivations and meaning. We need to now make the argument that this isn’t simply “more” data or somehow window dressing for the “real” data that is still numbersnumbersnumbers. We need to make the argument that what we learn from qualitative approaches is the stuff that can drive and sustain the kinds of changes that academia and Libraries need to make to be truly responsive and effective.

This is also not just about knowing particular research methods, but in being willing to try, to risk, to ask how to move from status A to situation B.

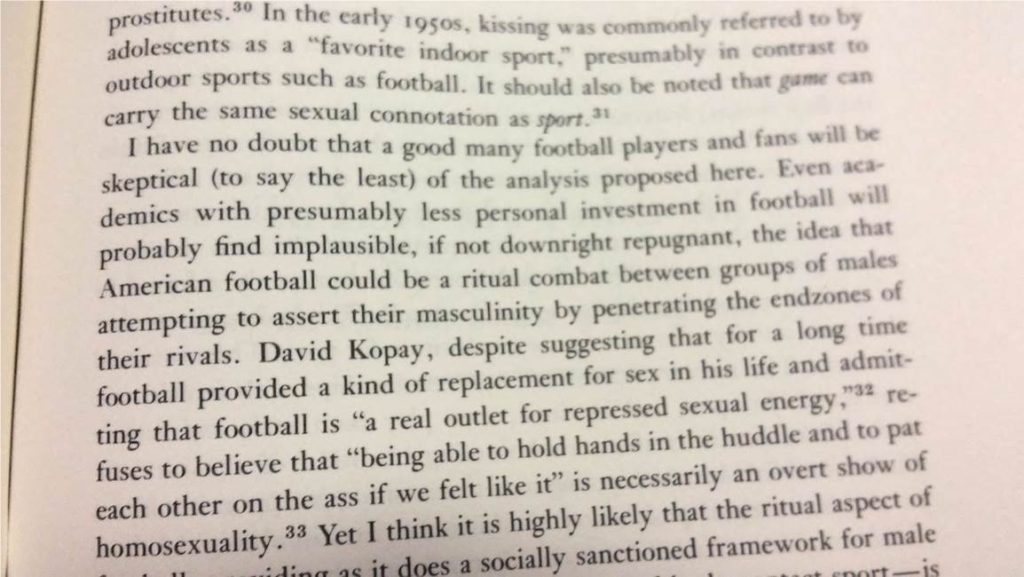

Photo of my own copy of this book. http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/308290.Interpreting_Folklore

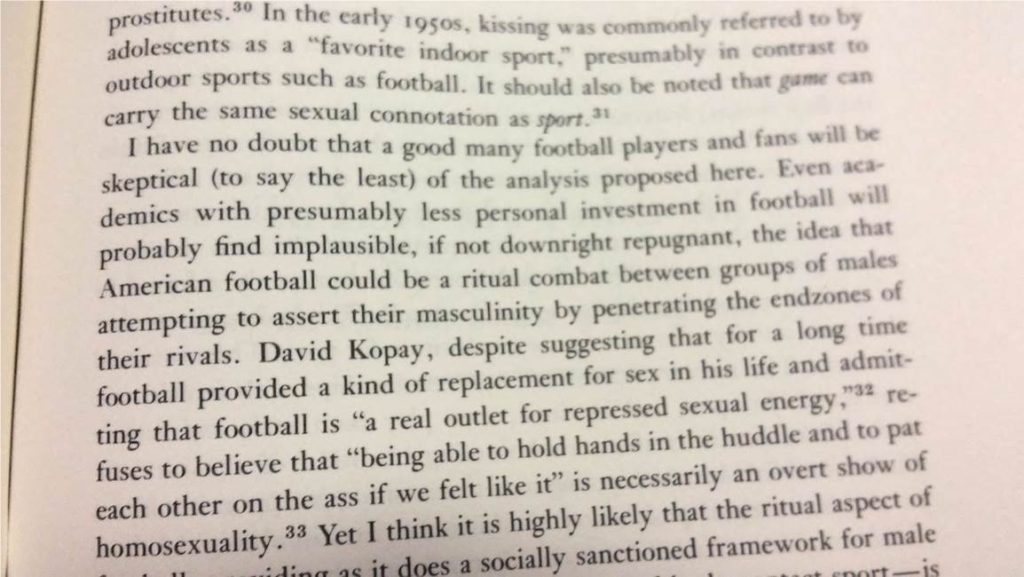

My PhD advisor, Alan Dundes, was a folklorist, one of the “young turks” of American Folkloristics in the 1960s, and he started off as a structuralist. He was taught that the collecting and classifying of folklore materials (jokes, tales, songs, and all other manner of folk genres) was the core work of folklorists. He swiftly grew weary of all of the collecting and classifying, the piling up of material in the absence of interpretation. He became a Freudian, and remained so the rest of his career, alarming and annoying and infuriating as wide a range of people as possible with article such as “Into the Endzone for a Touchdown: A Psychoanalytic Consideration of American Football.”

He really didn’t care if you agreed with him or not.

He wanted you to take a risk, make a case, say something interesting. And if you were wrong, particularly if you were his student, he expected you to make a new case with other interesting things.

Hanging out in front of Inka cut stonework at Q’uenko, Peru. Photo by the Elder Teen.

I have been with archaeologists in some form or another most of my adult life. My best friend in graduate school was an archaeologist (and she still is). I am married to Indiana Jones.

And I witnessed this thing where people would go into the field over and over again, constantly collecting data. Their presentations were full of counts and pictures and maps. They would spend their entire time talking about their methods and data and leave no time for interpretation and meaning.

But:

At some point, in applied work (like we are doing here at UXLibs, like I have to do in my work), it becomes necessary to stop collecting data, engage in interpretation, and start doing. Changing. To become an active organization, not just a reactive one. To do more than what is simply being asked of us, and gather and build a firm sense of who we are based on what we do, know, and understand.

So, what does “action” mean? It has to be more than band-aids, more than “the printer is broken/out of paper, fix it and put it back”

Action can be:

–describing and interrogating organizational structures (a necessary first step to change)

–representing missing points of view (which can then have an impact on what happens next)

These are things that are not traditionally “actions” but that do have an impact. To be truly transformative, you need to point these techniques towards big picture holistic shit. If this work is only ever about how you figured out what kind of furniture to buy, it’s not transformative.

Ethnographic techniques are doomed to produce just another bucket of data if we do not use them to their fullest extent. I am therefore making a cultural argument, one that requires leadership. Leaders need to be on board, and in the room (some of you were in the room with us at UXLibs, that’s so great).

Without the space provided by leadership, those transformations cannot happen.

What organizations allow for risk?

What organizations allow for change?

What does leadership look like in those organizations?

Is it only top-down?

[I asked the question]

Who in the room is on their library leadership team as reflected in the organizational chart?

[some hands]

Who in the room is a leader?

[some hands]

It’s the whole damn room, that’s why you are participating in UXLibs!

What is important here is not leadership, but NETWORKED leadership–if we are collectively working we are more powerful at effecting change. None of the work we are doing now with UXLibs II exists in a vacuum–much of it came out of UXLibs last year, but some pre-dated it, and there’s more stuff that’s not in this room right now. I would remind you here that the unit of analysis in anthropology is not the individual person, but groups of people. What UXLibs did last year was reveal the community of people working with these techniques and perspectives to each other. We are stronger as the network.

Leading change isn’t going it alone, it’s finding and building your team and then changing things together. Regardless of the organizational chart, regardless of institutional boundaries.

The most important kind of leadership is about creating space for change

Maybe leadership is also about creating space where “risk” is irrelevant–making it all about possibility. It’s about having a much wider space to feel comfortable talking about where we failed, where we got derailed. And to actually do the things that might fail, might not go quite as planned.

I am so proud of you.

Now there is more work to do.

Let’s do it together.

My front garden, 2016.

�