https://twitter.com/DonnaLanclos/status/740916557736333312

I just got back from Salt Lake City yesterday. I was and still am so pleased and flattered to have this invitation to speak to another group of librarians, another room of my colleagues inspired and challenged by the nature of instruction in and around libraries. This was my third (out of four) big talk of the Spring, and it was also the one I wrote the last, the one I struggled with the most. I knew I wanted to say something about vulnerability, but kept coming up against how to frame it, what was the point I wanted to make? I think in the end I came up with a point, but I confess that it was mostly in the improv around my notes, in that room this past Thursday morning, that it all came together (you can also see from the Storify ). Those who were in the room with me may reasonably disagree, of course.

I should also thank before I continue the people who helped me think this through, whether they realized it or not:

@edrabinski @davecormier

@tressiemcphd

@slamteacher @bonstewart

@jessifer @AprilHathcock

***************************

As an anthropologist who works in libraries, my fieldwork takes me beyond libraries into a wide variety of learning places. And those learning places are classrooms, cafes, parks, Moodle, Facebook, and Twitter. I spend a lot of time online and talking about being online, not just in my fieldwork, but in my academic practice.

Online is a place. It is not just a kind of tool, or a bucket of content, but a location where people go to encounter and experience other people. Places, online and otherwise, are made things, they are cultural constructs. Technology, and the places technology helps create, are likewise cultural constructs, and therefore: Not Neutral. They are human, they are made, they contain values.

I am not telling people anything that hasn’t been said before, but it’s worth repeating.

Libraries and Librarians aren’t neutral either.

I see some Librarians try to position themselves as neutral, supportive nurturing helpers, and those who try this are not always good at conveying it. I think the reason for that is that such neutrality cannot possibly be real–we are all human, we all have biases, we are not “objective” and pretending to be just allows us to deny our subjectivity rather than working through it.

[at this point I asked the room:]

How many of you have ever been told,

“I have a really stupid question?”

[lots of hands went up. Seemed like the entire room]

When people walk up and say, “I have a really stupid question,” It’s because they are preemptively signaling they are not comfortable yet. They don’t feel safe. So I’m wondering, how do we build, within libraries, and within education generally, places for people to feel safe?

And in thinking about places, I want to ask, where are librarians? Where do you want to be? Why do you want to be there? I am making an assumption here that If you are in online spaces, it is to connect, with each other, with students, (not because “it would be cool” please no not that).

I think presence in those places signals that you care, and value connection, and want to create safe spaces. How, then, does that affect practice? How do we think critically about practices such that we can make places feel safe?

How do you become trustworthy? Not as individuals, but structurally? What makes it make sense for students or faculty to come to you? To the Library? Where else is the library? Does the persistent question, “why don’t they come to us?” make sense if we are all supposed to be part of the same community?

What do you do to become part of your community? What do you do that is trustworthy?

And, also, how do you come to trust the people whom you are trying to reach?

How do you find them? How do you find out about what they are doing and why? Because it can be difficult to trust people you do not understand.

And this, actually, is part of the problem I have with these notions of empathy as some sort of prerequisite to action, to connection. I am troubled by the suggestion that you need to muster up empathy first before reaching out to students or faculty. (Not that I am opposed to empathy, I’m a fan of it in my life and work) Our students and colleagues are worthy of our respect, they have an inherent human dignity that means it is our responsibility to reach out, to try to connect, whether we have achieved empathetic understanding beforehand or not.

Perhaps, perhaps that empathy actually comes most effectively post-connection. Empathy is not a prerequisite, but an outcome.

Some of the work I do in my research and practice might point a way towards understanding the motivations behind practices online.

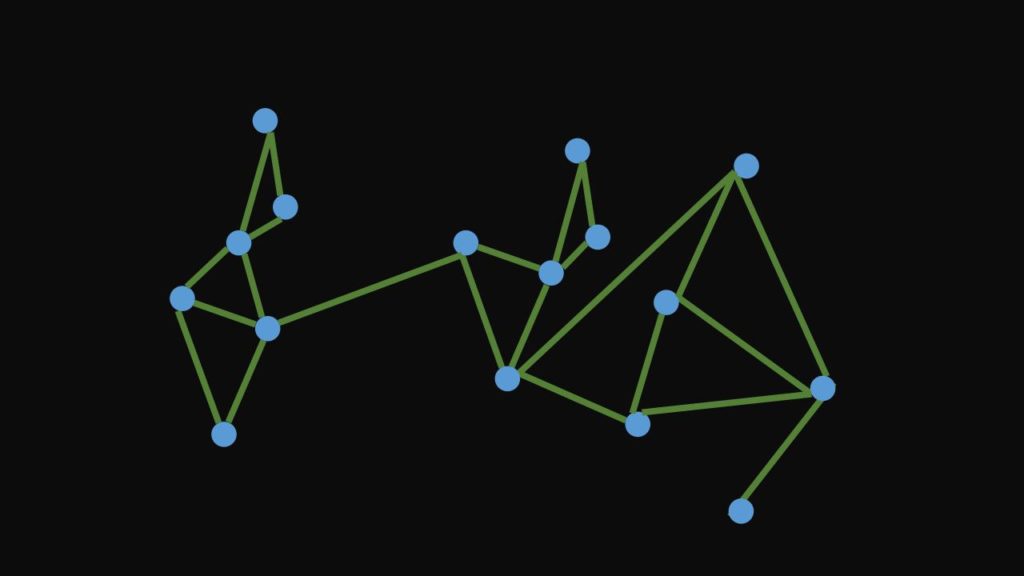

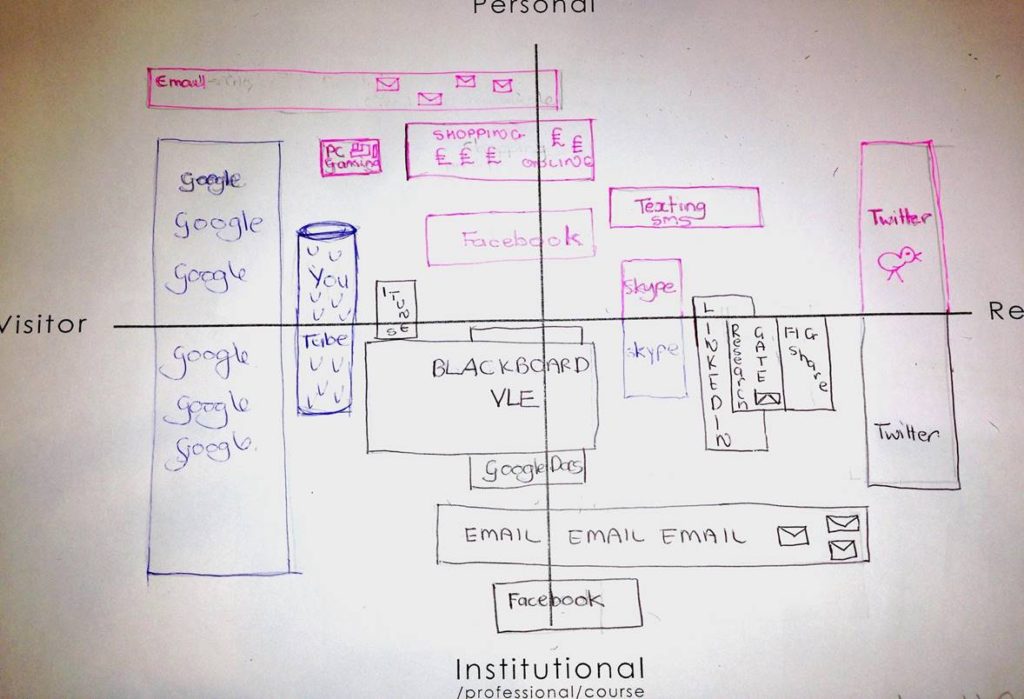

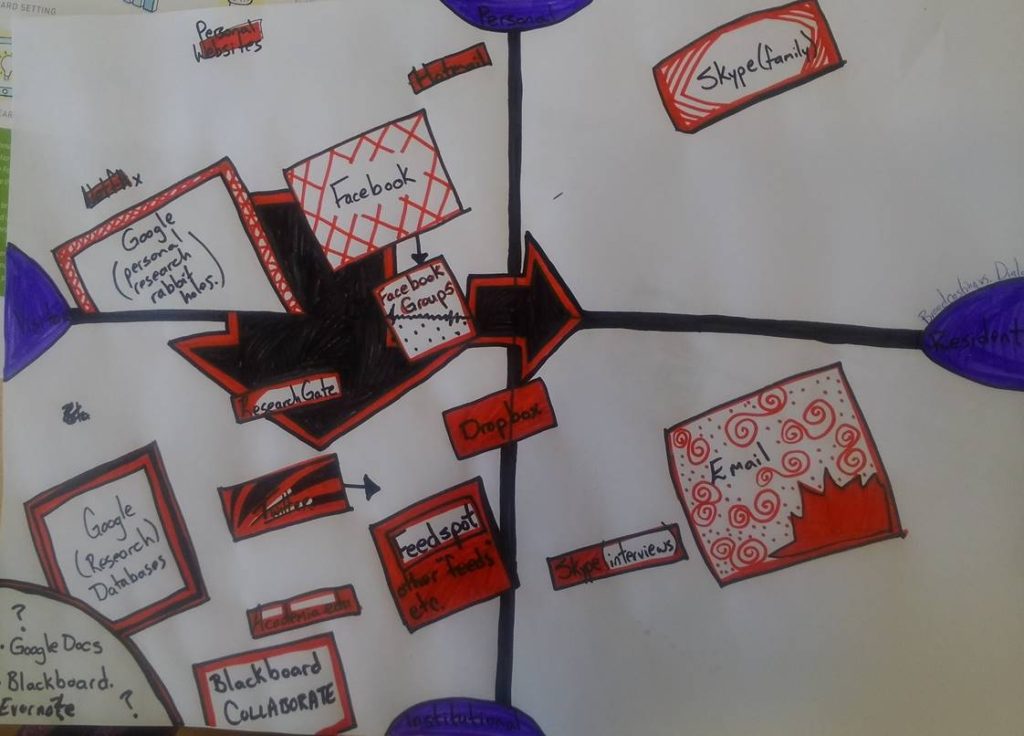

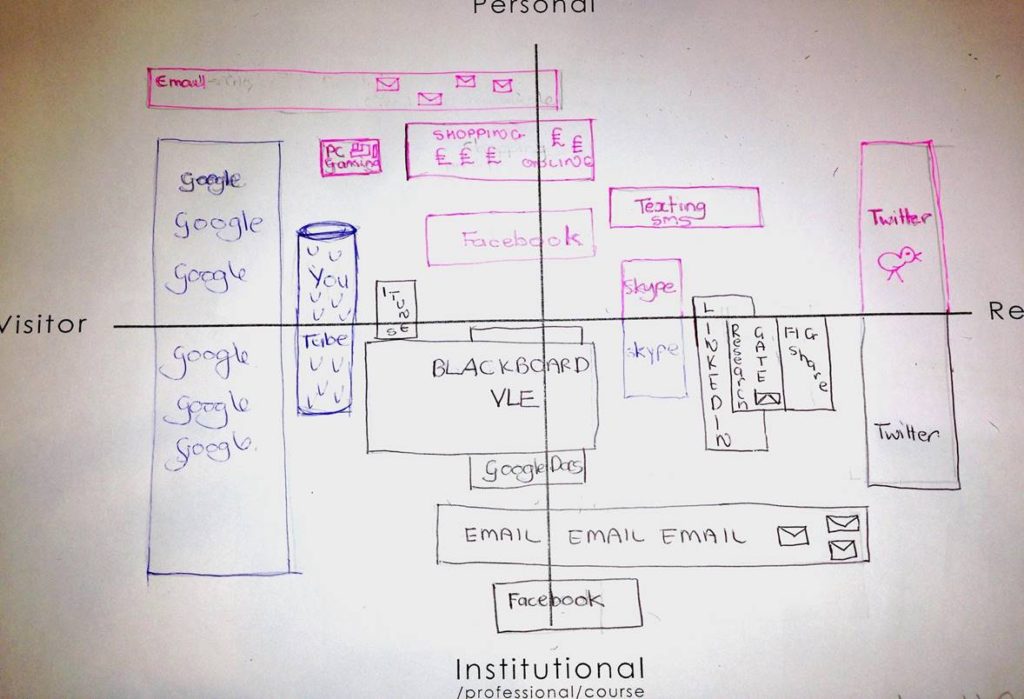

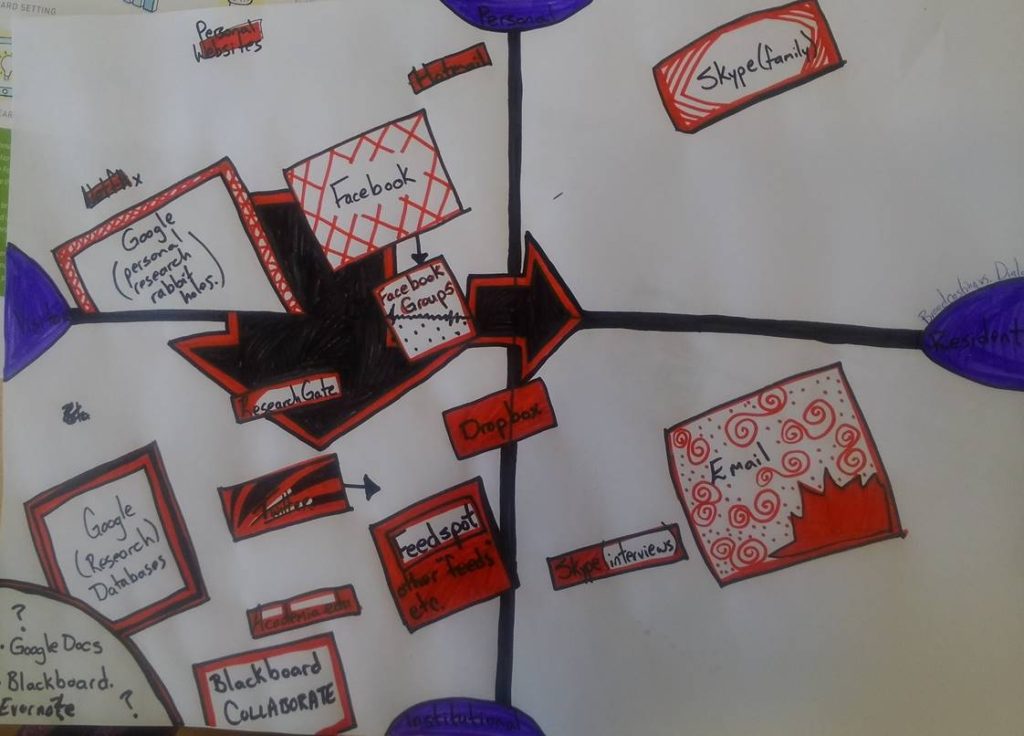

Visitors and Residents map, collected from one of the workshops we’ve conducted over the years. Visualizing practices, and online places, is a first important step towards understanding motivations to engage.

I have spoken and blogged before about mapping practices. In research and in workshops we can get people to talk about where they are online and also how it makes them feel. People feel about digital places in similar ways to feeling about physical ones–I’ve interviewed students who sigh deeply in dismay at the thought of their Facebook account, full of troublesome family members, or who smile in thinking about their Twitter community, configured carefully so that they can be who they want to be, feel how they want to feel, while in that place.

Online behaviors are not determined by the venue. Facebook is not always about what you had for breakfast, and Twitter is not always about politics. Each of these places, all of the new and old online places, are about people, and choices. So, mapping, as with the V&R maps, can show us where people are, but the important part is the conversations that are generated, about why they are there (or not).

I think about the emotional associations of institutional spaces, for example in usability studies of library websites revealing the embarrassment and frustration students can feel at not being able to wrangle the website. In fact, they frequently blame themselves for the tech failure, apologize to us for our crappy websites. They say they will try again, but when they are away from us, why would they go back? Who voluntarily goes back to some place that makes them feel stupid?

During the Twitter-based #digped discussion in mid-May, there was a discussion about how to make ed tech more human. This tweet I’ve captured points to some of what I have been turning over in my head about digital and presence.

When thinking about instructional online spaces, I’d like to ask (and I’m far from the only one) how to make them human as well as positive? How do we build in access to other people, and not just provide buckets of content? Where are the people in your online learning environment? Are they connected to each other? In my experience, students find their human connections outside of the institutional learning environment–they are on Snapchat, on Instagram, in Facebook and Twitter. So we should continue to think about the role of digital places, outside of institutions as where connections happen.

We need to continue to think about identity, and how it plays out online. Where and how do we develop voices online?

I have been thinking the role of vulnerability–it troubles me lately, because I often see it approached in terms of personal vulnerability, of some sense that sharing your personal life at work is necessary, so as to give people a “way in.”

In my own practice, I’ve made deliberate decisions to share parts of my personal life, on Twitter, in my blog. I approach it as a political decision as much as anything, a result of what I think needs to happen around the representation of women as professionals and academics. And things I’ve written can indeed be interpreted as a wider call for more people to be “personal” online, so as to be human, and therefore accrue a different kind of credibility in the new academic spaces of the Resident web.

“Acquiring currency can be about whether a person is perceived to be vulnerable, not just authoritative, alive and sensitive to intersections and landscapes of power and privilege: As Jennifer Ansley explains, “In this context, “credibility” is not defined by an assertion of authority, but a willingness to recognize difference and the potential for harm that exists in relations across difference.” In other words, scholars will gain a form of currency by becoming perceived as “human”…rather than cloaked by the deliberately de-humanised unemotive academic voice. This is perhaps because the absence of physical embodiment online encourages us to give more weight to indications that we are assigning credibility to a fellow human rather than a hollow cluster of code. We value those moments where we find the antidote to the uncanniness of the disembodied Web in what we perceive to be indisputably human interactions.”

Lanclos and White, “The Resident Web and Its Impact on the Academy,” Hybrid Pedagogy, 08 October, 2015

Who is a scholar? Who is a professor? Who is a teacher? The many paths we take now didn’t always exist, and there are indeed political as well as pedagogical reasons for revealing those narratives (as I have, in talking about mine).

But I wonder, how do you reconcile that with the narrative of “risky” online environments, and how faculty and students need to be “cautious?” How do you balance the need for a kind of vulnerability with desire for “safety”–how is that possible? What does “safe” mean?

What constitutes vulnerability online, and for whom?

Who gets to be vulnerable? What does that mean?

Who is already vulnerable?

“Risk-taking” is so often framed as a positive thing, especially when people in a position of privilege engage in it. But when the intersections of our identity place us in more vulnerable categories, ones other than white, straight, male, cisgendered, middle (or upper)-class when does “risk-taking” segue into “risky?” When do our human vulnerabilities get held against us? This is about context–who is classed as positive risk-takers when they make themselves vulnerable, who is classed as “risky” and perhaps necessary to avoid, someone who makes people uncomfortable.

So, what price “approachable?” How much do we strip ourselves of ourselves so that people are comfortable, so that we are not “risky?”

This, I think is the tyranny of NICE–I see this especially in libraries, wherein “approachability” can be shorthand for “seems enough like me to be safe” How do we create environments where unfamiliarity doesn’t have to feel risky? Where “discomfort” isn’t a barrier to engagement or thinking?

How do we get a diversity of “safe” people into our networks, who do not discount us as “risky” in our vulnerabilities?

In particular i want to ask this question:

What does it mean when we ask Students to be vulnerable online? How is it different if they are women? Black? White? Brown? LGBT+? Fill in the category of your choice here.

Because some of us show up more vulnerable than others. Our identity is not just the categories and characteristics we self-identify with, it’s the boxes people try to place us in. it’s involuntary vulnerability, the people we are perceived to be become a way to dismiss us, our expertise, our content. Structural and personal vulnerability can’t be shaken off, and maybe we don’t owe anyone our personal vulnerability. Maybe our students don’t owe us personal vulnerability.

Vulnerability doesn’t have to be personal.

I think about professors giving phone numbers out to students, back before social media ubiquity. Choosing to give out home phone numbers, or even cell phone numbers wasn’t something everyone did, it signaled a particular approach to boundaries and the role of professors in student lives. What is the online equivalent? Is it friending or following on social media?

I wonder what are other ways of being present and human to students without violating important boundaries yourself?

I don’t think that kind of putting yourself personally out there is mandatory. Personal narratives don’t have to be the default. You don’t owe anyone your personal story. And sometimes just your existence is story enough.

We do owe them professional vulnerability. That way lies inclusion–for our colleagues and our students. Professional vulnerability can model the kind of society that we want them to have. We need them to be flexible, transparent, and to expect that from their professional and civic networks going forward.

So what would that kind of professional vulnerability look like?

Libraries have traditionally expressed “service” in terms of seamlessness–systems that don’t need explaining, for example. And from a UX perspective, that’s one thing. But in an instruction context, that’s problematic. Seamlessness doesn’t signal a way in. iPhones don’t tell you how they are made, they just expect you to use them. How do we build educational environments, both digital and physical, that give people a way in? In to the course, to the library, to the discipline, to the University?

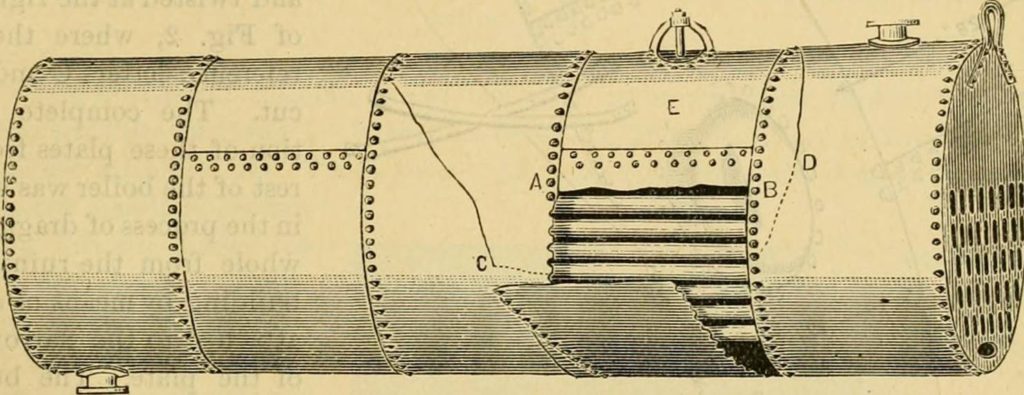

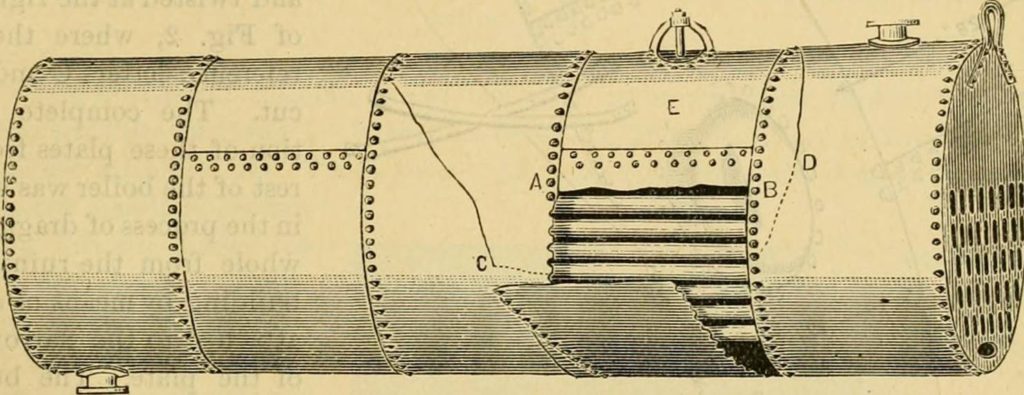

One answer might be in engaging with seam-y (“see me”) practices and pedagogies. Showing the seams, being open about how educational experiences and scholarly content are produced. Academia is a made thing, we can show students the seams, and allow them to find their way in.

Seams showing how the locomotive cylinder is put together. Image from page 180 of “The Locomotive” (1867) Internet Archive Book Image Flickr Stream: https://flic.kr/p/ovuPbj

I see examples in many places. Including the rhizomatic learning work coming from Dave Cormier. In his connectivist approach to education, he argues that:

“What is needed is a model of knowledge acquisition that accounts for socially constructed, negotiated knowledge. In such a model, the community is not the path to understanding or accessing the curriculum; rather, the community is the curriculum.”

“In the rhizomatic model of learning, curriculum is not driven by predefined inputs from experts; it is constructed and negotiated in real time by the contributions of those engaged in the learning process. This community acts as the curriculum, spontaneously shaping, constructing, and reconstructing itself and the subject of its learning in the same way that the rhizome responds to changing environmental conditions.”

Teaching a class where you admit that you aren’t quite sure where things are going, where you are clear in not knowing everything, that is professional vulnerability. Instructors who construct their authority in the classroom around knowing everything, or at least knowing Way More Than Their Students about Everything, are at risk of #authoritysofragile, of that moment when it is revealed that of course we don’t know everything, and the authority is shattered. We can avoid those shattering moments by never pretending in the first place to know it all. Positioning ourselves confidently alongside our students as we explore things without being sure of outcomes, that’s powerful, that is seam-y, that is professional vulnerability.

If you read this blog you’ve seen this map before. This workshop participant annotated her V&R map with arrows indicating where she wanted to move her practice, mapping the trajectory of the changes she wanted.

In the V&R workshops we conduct we ask people to annotate their maps, to show where they are willing to move and change, and even discontinue what they are doing. The epiphanies that happen when people realize this thing they have been doing doesn’t serve them especially well can feel like admitting a mistake. These conversations reveal emotions that these places and practices engender, and those revelations are a form of professional vulnerability.

Open practice is a kind of vulnerability that reveals the seams of academic work. I am open in my own practice, in sharing rough drafts via Google Docs, in blogging half-formed ideas, in Tweeting even less formed ideas. If you look at my blog from when it first started my voice was very different than what it is now. I am never finished, my work is never seamless and complete.

What can we do in our own practices to create spaces where the seams of academia are visible? Create places where our students can see how and where they fit? The possibilities for our students finding where they can get in are contained in the spaces we do not fill with content, or cover over with seamless interfaces

The work of teaching and learning is challenging, and when we talk about seamlessness we are lying about what education is supposed to be. The challenge is in doing the things we don’t know yet, and how will our students learn that if we do not? If we do not model our own unformed and unfinished practices, how can they even know that is what happens? How can they imagine themselves doing it?

Digital affords us different ways of revealing the seams, the mess of our academic projects. We can, without revealing ourselves totally, still reveal process in a way that makes it clear that academia is a cultural construct, made by people not entirely unlike our students. Tools and places are out there such as Hypothes.is ,GoogleDocs, Twitter, blogging platforms. Facebook groups, Instagram, Pinterest, ephemeral contexts such as Snapchat. The point is not the specific environment or tools, but in the possibilities to connect, and capability of revealing process along the way.

We can highlight the importance of engaging in unfinished thoughts, in exploration. Where a .pdf is seamless and a finished product, an invited GoogleDoc is seam-y and in process, perhaps never entirely done.

Libraries have a history of engaging with process, not just content. Libraries are good at this, their particular area of expertise is in navigating, framing, and evaluating content (in its myriad forms). Open practice, professional vulnerability around the processes of academia, this is an opportunity for Libraries and Information Literacy and Library Instruction to shine.

My friend and colleague Emily Drabinski writes marvelous things, and one of her latest, a co-authored piece with Scott Walter, “Asking Questions that Matter” challenges us to articulate not the value of libraries, but the values within libraries, coming out of libraries, of library instruction.

So I want to end, as I usually do, with questions.

What values are you expressing with your instructional approaches? How can you express them digital places?

What is the role of vulnerability for you? How can you protect yourself, model protection for your students, and still achieve seam-y pedagogy?

What would that look like?

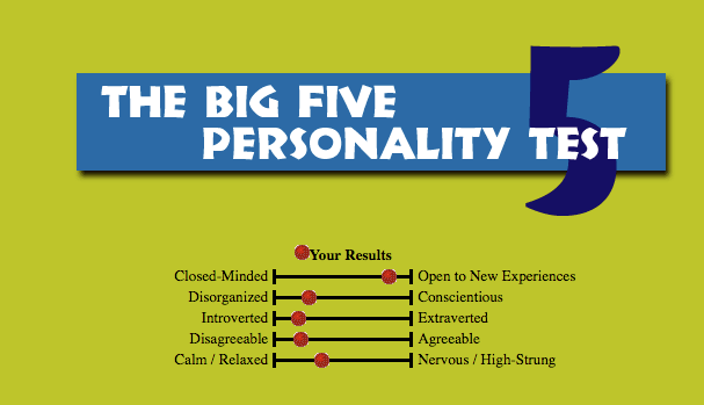

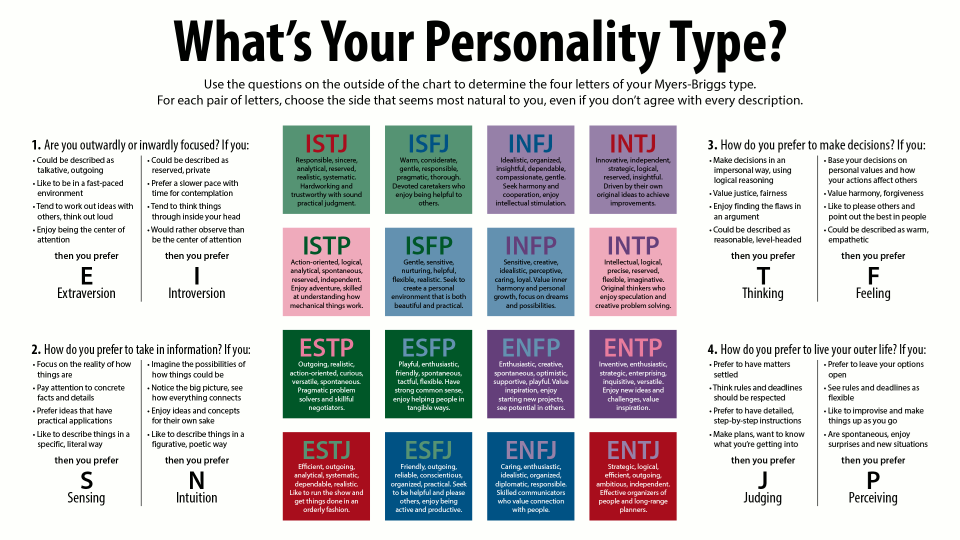

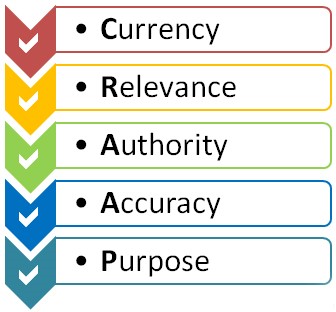

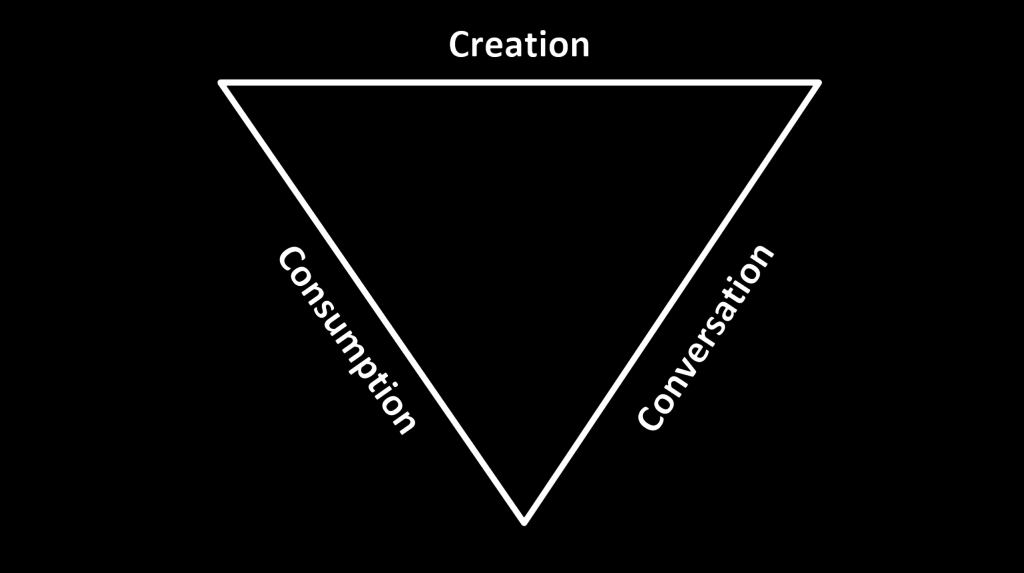

And early on, I was working within the framework of Visitors and Residents, in part because we thought it would give people a way to push back against the problematic framework of Natives and Immigrants, give them different ways of talking about themselves and their practice that were less damaging. What we found, though, was that people started to pigeonhole themselves in the different framework that we gave them, because they were still talking about identity, about who they were, rather than what they did. So, this triangle is our attempt to give people a way to center themselves within their practice, to map themselves within a framework that does not try to pigeonhole them.

And early on, I was working within the framework of Visitors and Residents, in part because we thought it would give people a way to push back against the problematic framework of Natives and Immigrants, give them different ways of talking about themselves and their practice that were less damaging. What we found, though, was that people started to pigeonhole themselves in the different framework that we gave them, because they were still talking about identity, about who they were, rather than what they did. So, this triangle is our attempt to give people a way to center themselves within their practice, to map themselves within a framework that does not try to pigeonhole them.