|

Listen to this post

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Thanks to everyone who attended #GlosLearn17 yesterday. Check out the @Storify by @davidwebster https://t.co/1mZokiAmme pic.twitter.com/2Lcmk4jTNv

— University of Gloucestershire (@uniofglos) June 15, 2017

Last week, on the day that the TEF was originally supposed to be released, I delivered a keynote to the lovely and engaged crowd at the University of Gloucester’s Festival of Learning (you can see the conversations that ranged throughout the day at the #GlosLearn17 hashtag on Twitter, see the Storify here, and read two blogs thus far from David Webster and Lawrie Phipps about the day).

Today, on the day that the TEF results are actually released, I have the time to blog my talk.

(twice, it turns out, because the internet ate this post once already)

First, of course, thank you to David Webster for inviting me, and giving me the chance to share my thoughts.

I wanted in this talk to discuss the work I’ve been doing in collaboration with UNC Charlotte’s center for teaching and learning, how that fits into my larger body of work, and what I think is at stake when we talk about teaching and learning practices in the education sector. Within the #GlosLearn17 audience were not just HE folks, but people from FE, colleges, and primary and secondary education. While my examples here are from HE, I think they have implications for the sector as a whole, and I’m keeping all of the various locations in mind when I think and talk about this.

As always, I come at this topic as an anthropologist, and while my job is situated in the library, my body of work is about far more than the library. I am a researcher of academic practices (and the motivations behind those practices, and the contexts in which they occur). As such, my work is not bounded by the institution, any more than the lived experiences of our students are.

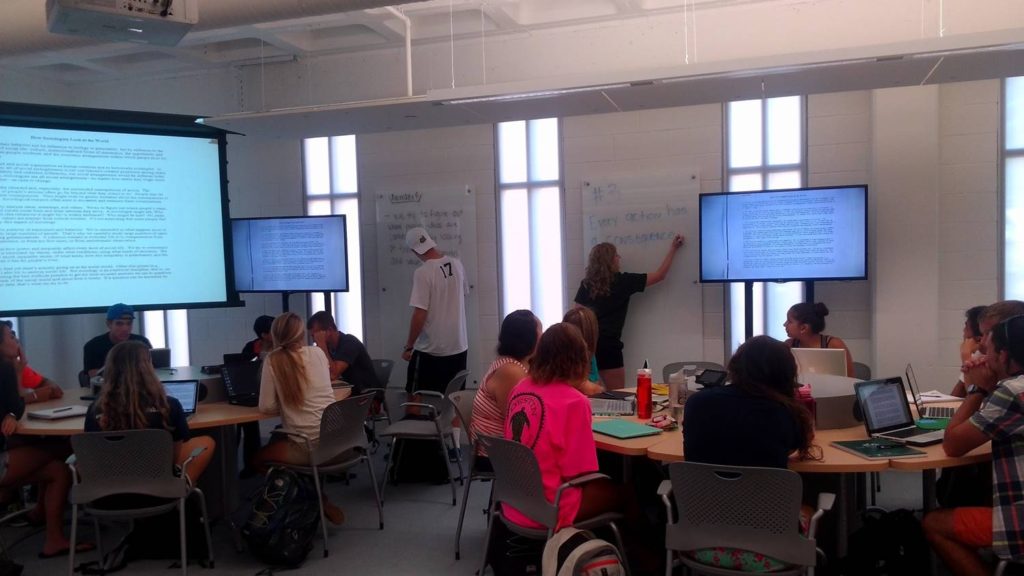

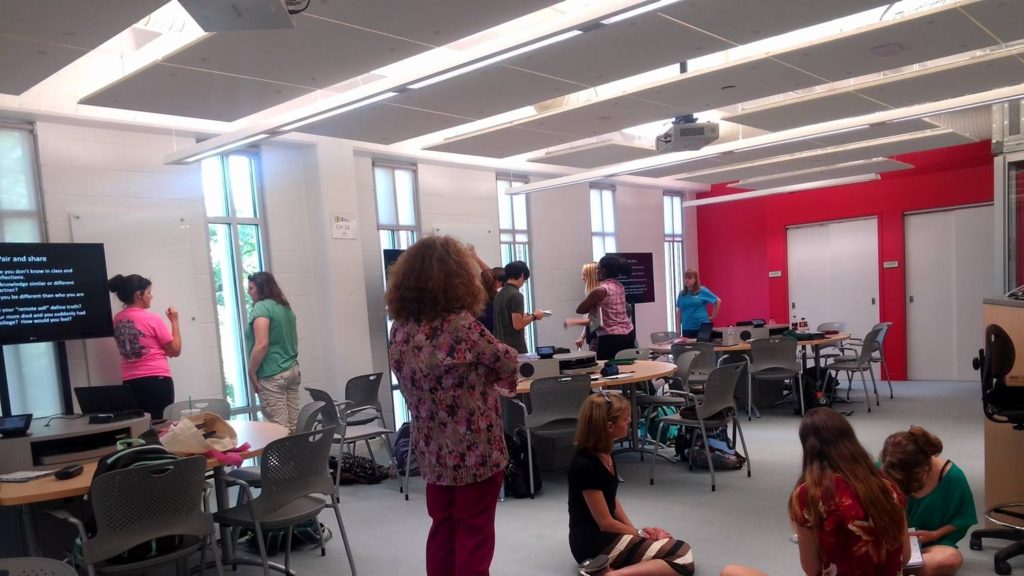

I have blogged about the Active Learning Academy at UNC Charlotte before, and won’t rehearse it all again here, but I did, in the talk, go over what we had done as a case study for paying close attention to teaching and learning practices. My role in the collaboration has always been to help observe and analyze the behaviors we saw in the classrooms, and also to help facilitate conversations among faculty and students about what’s working (and not) in the active learning environments.

I try, when I talk about these spaces, not just to point to the physical renovations (and the funding from Academic Affairs) that gave us these spaces, but to emphasize the importance of the continuing professional development community that the CTL and our Office of Classroom Support (and the continuing funding that requires). I also point out that the initial design of our classrooms is based on a great deal of research on the part of my colleague Rich Preville, who drew in particular on the SCALE-UP model.

This shows some of the kind of work that’s possible in rooms like these–even in the first year of our Active Learning Academy, we had faculty members who were practiced in active teaching pedagogy practices, even in rooms that did not facilitate them (such as lecture halls). The primary work of the Active Learning Academy leadership team was to provide faculty a chance to talk to and learn from each other about active learning. The CPD piece was at least as important to us as the building of the rooms–we knew that the rooms were only the beginning, if what we wanted to do was to transform teaching and learning practices in a sustainable way.

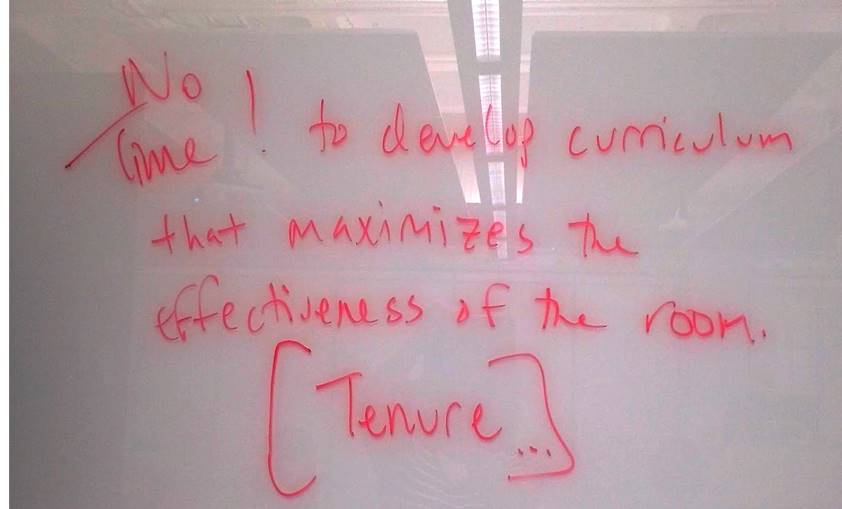

In this CPD environment we captured some of the anxieties of the faculty:

“No time! to develop curriculum that maximizes the effectiveness of the room

[Tenure…]”

Faculty expressed concern about the time necessary (and not always available) to really sit down and work through their teaching practices to best align with active teaching and learning goals and with departmental mandates about delivery of content. This is a real struggle–teachers who want to explore active teaching and learning are often told that this is in opposition to the teaching of a particular subject. The “education is a process” piece is in tension with the “education is the delivery of content” piece, and the latter has a tremendous amount of traction, institutionally.

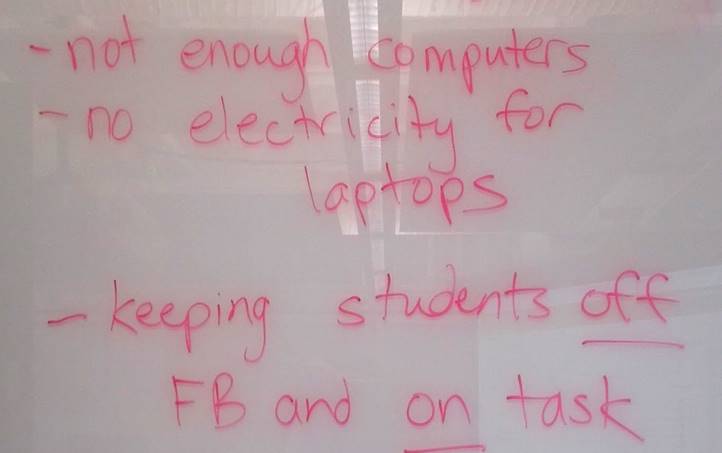

“–not enough computers

–electricity for laptops

–keeping students off FB and on task”

Present in the conversations were notions of scarcity–both of resources and of attention. Will the room be enough? How can we focus? What do we focus on in rooms like this? How do we get students to pay attention to ME? Faculty under the impression that effective teaching requires students to pay attention to their performance as a lecturer (rather than engaging with the substance of the course) struggled here.

There was also an ever-present concern about the need to “train” students to use the technology (another blow to the “digital natives” canard). I’m afraid we set this one up, in the first year, by front-loading the faculty orientations to the active learning classrooms with “tech training.” We made the mistake of starting with “what button to push” rather than centering the approach around teaching and learning (we have since fixed that)

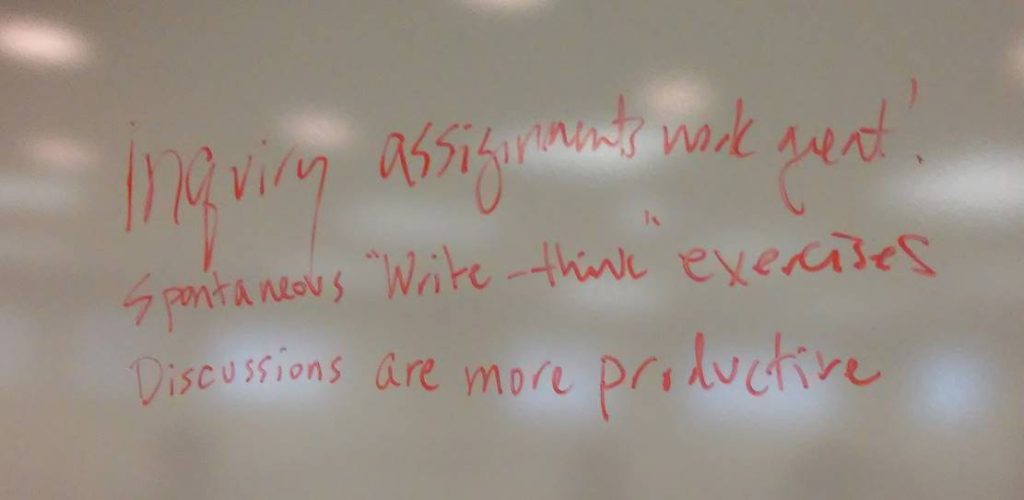

Positive things that emerged from these conversations were around what kind of teaching faculty could do, and what sort of learning they facilitated and witnessed.

“Inquiry assignments work great!

Spontaneous “write-think” exercises

Discussions are more productive”

Faculty can see real impact in their classrooms with these techniques, even as they are concerned about what else they could be doing, and how much more they can push their practices. Faculty see more engagement and more interest, not just from their students, but from themselves.

There are at least 25 years worth of research pointing to active teaching and learning as more effective educational practices–far more research than points to the efficacy of lecture, for instance. We have instructors who engage with these practices even when the physical spaces they have to teach in do not facilitate them. They figure out ways to be modular in their approach, because the institutional spaces of the university do not universally have “active learning” as their default.

So why, at UNC Charlotte, or at any university engaging with active learning practices and spaces, aren’t these the default? What right do we have as educators to not have this be the default? Whether or not we engage in the active learning agenda is a social justice issue.* We have an ethical obligation to engage with these practices.

Why do barriers exist when we know that this is a better, more effective way of teaching?

Exercises like the TEF are symptomatic of the tensions between what is effective, and what is being assessed. Extra-institutional forces continue to define education as filling students with buckets of content, rather than framing education as processes that can be engaged in within the context of any number of different subject matters. Institutions and instructors are assessed/evaluated on outcomes, not processes. Teaching strategies are homogenized across Quality Assurance frameworks** without talking about diversifying and widening access to education, expanding the ranges of effective practice, or about processes of education and the complex ways that can prepare our students to be citizens. Checkboxes and metrics reduce teaching and learning to commodities that we sell our students. We see this in higher education, especially in institutions that are historically positioned as “teaching” institutions. The prestigious, research-centered institutions are the ones who are most likely to have the privilege to evade frameworks like the TEF, and also some narratives of employability.

The fees system that is relatively new to the UK is old news in the US. And the narrative of skills and jobs and credentials and what kind of degree will “get you a job” isn’t new in the US either. In her book Lower Ed, Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom points to the systemic, structural problems underlying the rhetoric of “skills” education as a solution for a crappy economic situation, and a stratified, racist society. Lower Ed is an ethnography of for-profit institutions of further education (that is, those for whom student fees go to profit executives and investors rather than get put entirely back into the running of the institution). Tressie makes the compelling case that these institutions are the logical progression of “employability” narratives, setting up students to pay more money and go back again and again to get credentials to make themselves marketable.

She furthermore makes the point that Lower Ed is a state of mind, not just a kind of institution. And therefore the book Lower Ed contains lessons for all of us in higher and further education. The responsibility of universities is not to provide jobs–that’s what the economy is for. If we want to improve our students’ prospects, says Tressie, we fight for jobs programs, we work within political and economic systems. Education is potentially a collective social good, but we have lost that thread, she argues in her book, we have allowed it to become commodified into an individual good. Making education into “training” is Bad Education. It is not the kind of education that results in informed, productive, engaged citizens.

Education cannot just be (never has entirely been about) filling students with content, but is (should always be) about engaging in processes of critical thinking, learning together, of knowledge creation as well as consumption and critique. The passive consumption of content is what has got us here, in this particular moment, in this political situation, in my country, and in the UK. This is about more than what happens in educational settings, this is about what is at stake for our communities.

In the same way that I find Dr, Tressie Macmillan Cottom’s work an antidote to employability narratives, I find Dr. Bon Stewart’s work an antidote to the notion of education as limited to “what we do in school.” Her recently formed project, Antigonish 2.0 hearkens back to an adult education experiment of the 1920s-40s in Nova Scotia. I am going to quote from Bon’s blog here:

“Its vision was as education-focused as it was economic, with an emphasis on building literacy as an avenue toward civic participation. The Antigonish Movement addressed people’s poverty and lack of agency by creating collaborative capacity for pushing back on the structures of their disenfranchisement.

I want to try it again. But I want to focus on a different sort of poverty and disenfranchisement: our current, widespread incapacity to deal with our contemporary information ecosystem and what the web has become. The attention economy and the rising specter of “alternative facts” create demographic and ideological divides that operate to keep all of us disenfranchised and disempowered. Antigonish 2.0, therefore, is a community capacity-building project about media literacy and civic engagement.”

The point is that education cannot simply be about what happens in universities, colleges, schools. Education is about more than school, or work, it is about our lives, in their entirety. The problems we face, of politics and economy and of society at large, these are problems and contexts that we must tackle collectively, and with all of the capacities that process-centered education can build.

I have been thinking in terms of citizenship. There’s a wide-ranging semi-structured conversation on digital citizenship happening at the #digciz hashtag on Twitter, on YouTube, as well as in numerous blogging spaces, and I encourage you to check those out. When I talk about citizenship, I mean it very broadly, in terms of civic participation in service of a common good. It’s a social value, not an individual one, for me.

As a community of educators, we need to collectively move practices to a place where we can do what we know is effective. We have that responsibility, and we need to figure out how to do this– not just for the education sector, but for our countries, our communities, our people however we define them. How do we practice education in a way that allow us to access social good, not just valorize education as an individual good to be exchanged for jobs?

What are we telling our students, through our practices?

What are we telling each other, as colleagues and peers?

https://twitter.com/Lawrie/status/874718669821140994

*e.g. Freeman, Scott, et al. “Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.23 (2014): 8410-8415.

** BURKE, Penny Jane, STEVENSON, Jacqueline and WHELAN, Pauline (2015). Teaching ‘Excellence’ and pedagogic stratification in higher education. International Studies in Widening Participation, 2 (2), 29-43.