So, I’ve been thinking about mapping, not just because I have these maps I collected at UCL in March, but also because I’ve been thinking more about the utility of processes such as the V&R mapping that we have been using in our research. What Dave White has said to me is that mapping exercises like V&R give us processes to offer people, but no answers, that in fact people use the processes to find their own answers. It’s not our job as researchers to provide answers, in this framing, but to ask effective questions that prompt people to find their own way. As usual, my first instinct was to be annoyed by this. My annoyance stems now from thinking that Dave is probably correct.

I am often asked for Answers when I give talks about what is going on with faculty and students and libraries and education generally. While it’s tempting to try to provide Answers, I think that I’m much better at coming up with more questions. And ultimately, that might be more useful, as I think I’m probably not the one who should be Answering.

Cognitive mapping exercises at UNCC and UCL reveal people’s learning landscapes. Thinking about cognitive mapping in the larger context of mapping exercises made me consider the possibility of a discussion around the cartography of learning, that is, all the different ways we try to capture and visualize what people are doing when they are learning. We are mapping (or having people map for themselves) what they perceive to be there, and in the mapping we receive a revelation, not something predictable, or predicting. We also do not have a precise rendering of actual practices, but an interpretation of practice. How can we use the maps to build more deeply observed pictures of behavior? How do we deal with the fact that maps are only ever representations of a lived reality? “The map is not the territory.”

If the Google Earth of Bloomsbury looks like this:

And the Google Map looks like this:

And the Tube map, itself a concept map of sorts, looks like this:

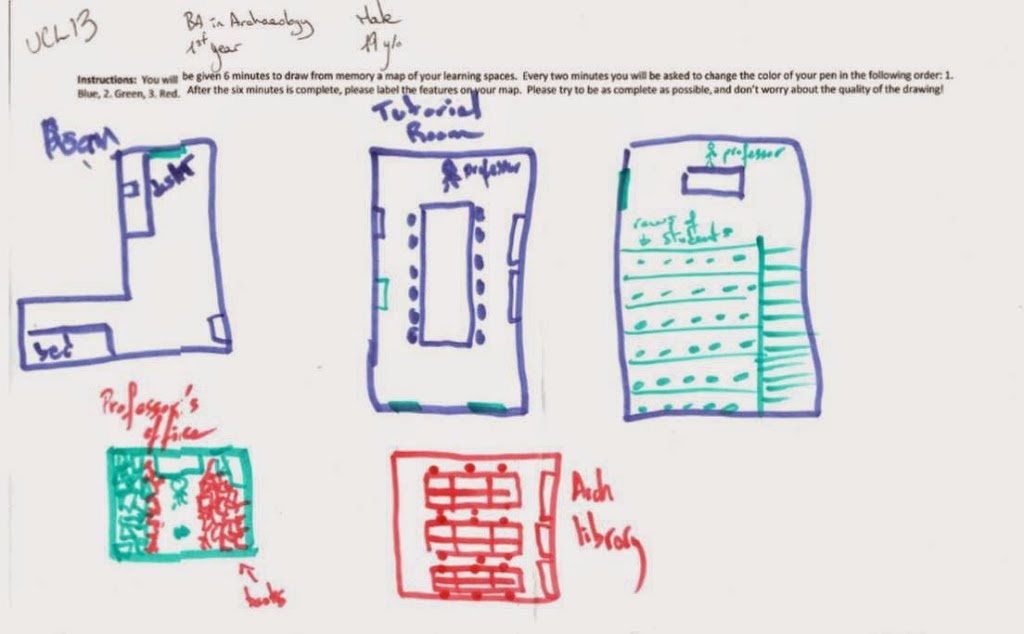

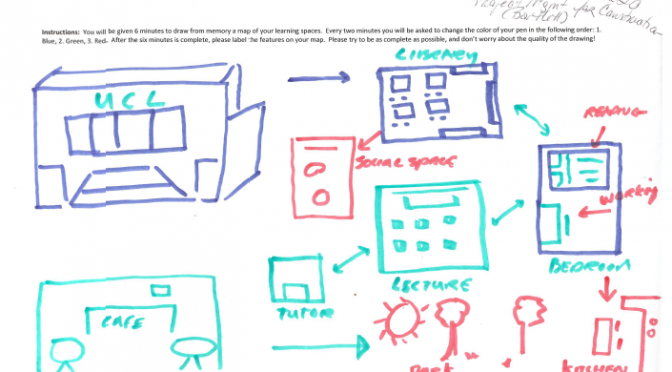

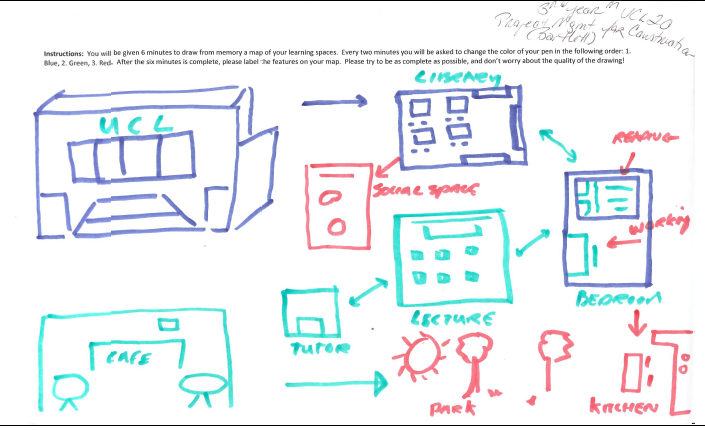

Then we have a map like this one I collected in March:

For this first year archaeology student, UCL is a series of spaces isolated from each other, but connected by the fact that he needs to do things, different academic tasks, in each space (my favorite is the professor’s office in the lower left, filled with clutter except for a small clearing in which professor and students can sit to talk). I can see that these spaces are connected, but he does not represent them that way.

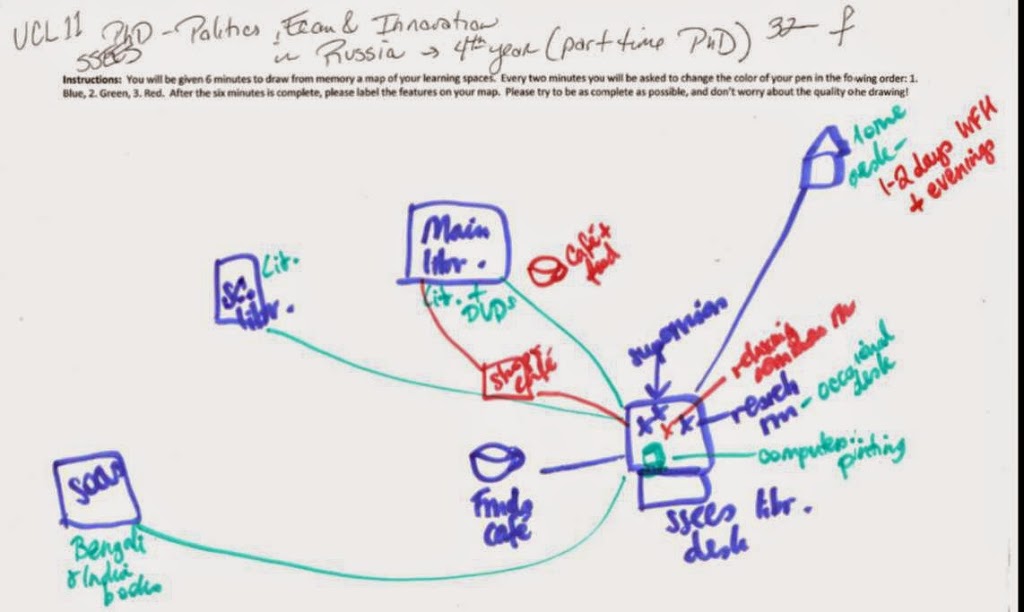

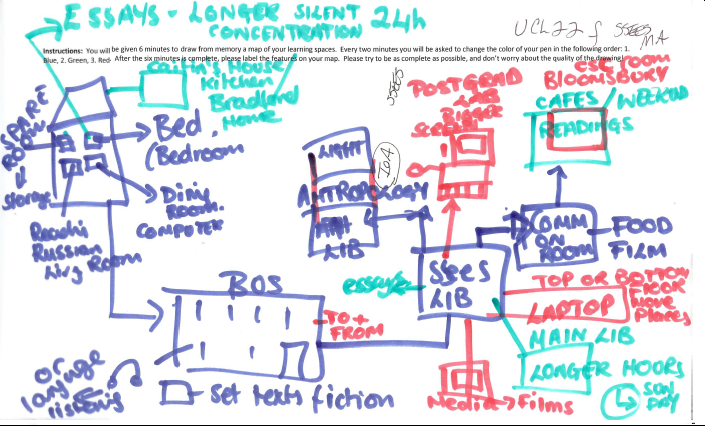

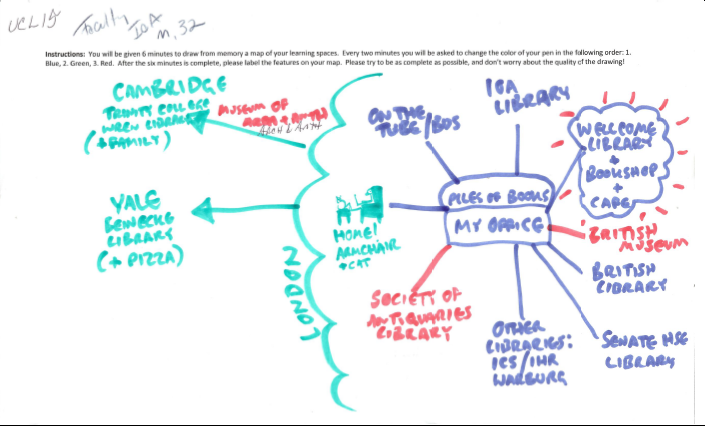

This PhD student has drawn lines indicating how connected her spaces are, the ones in Bloomsbury, and the ones that are not. She annotated the map with notes about the technology and particulars of the work she does in each space, which places have particular resources (content and people) she cannot get anywhere else, and marks cafes with the cups of tea or coffee that she goes there for. She has glossed her own map–I can bring my own spin to things (and I will), but there is already interpretation here.

Cognitive maps, the V&R maps, these are all contributing to a kind of cartography of practice. In the case of the cognitive maps I’ve been collecting from faculty and students, the mapping is an emic process, where the the practitioners themselves represent their own practices as best they can.

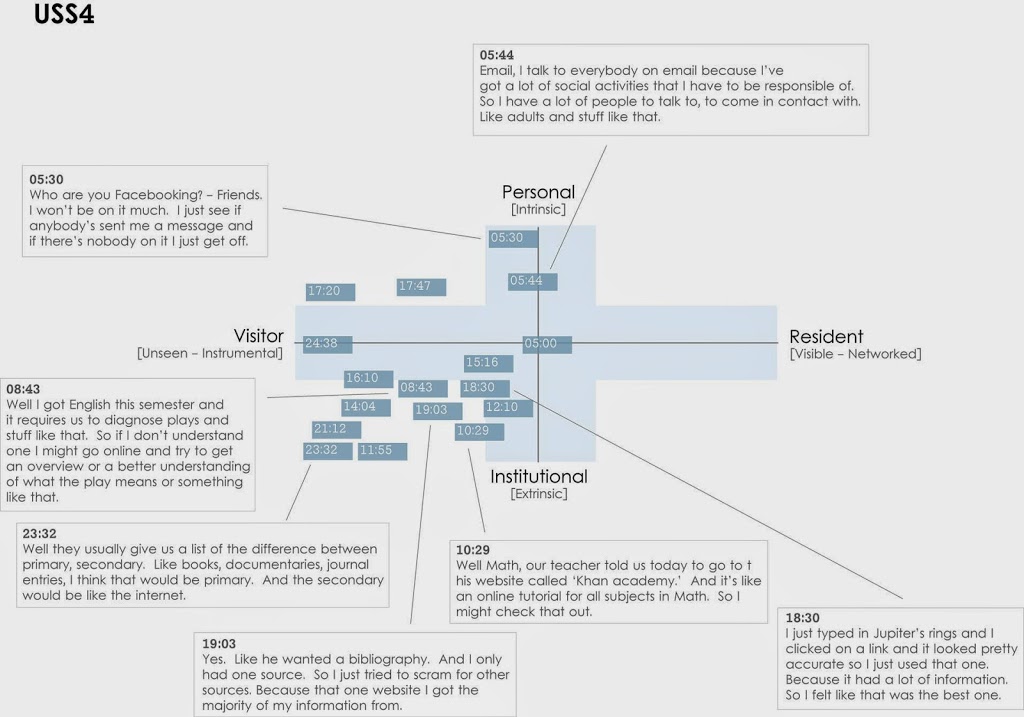

In V&R mapping workshops, people map their own practices, but they are also asked to think about the practices of others. We’ve done that in the V&R research project as well, for example in this map, where we took practices invoked by the interviewee and plotted it in the V&R continuua:

|

| map by Dave White and Erin Hood. |

Here we engaged in the mapping of the traces of practices of others as an analytical tool, engaging in an etic process, imposing our interpretation of meaning from the outside looking in.

They map, we map, and possible meanings and definite questions can emerge from the process of mapping.

I have been working my way through Latour’s Reassembling the Social with a Twitter group of colleagues, and am only part way through. Latour invokes the “cartographies of the social” (p.34) when discussing the need for researchers to pay attention to actual practices, to the lay of the networks in play, and to de-emphasize the interpretive leap while still in the process of figuring out what it is we are looking at. I am also struck by Latour’s insistence that the best social science cannot privilege the perspective of the researcher, but must be embedded in the meanings and practices generated by the people being studied. This, to me, is a plea for anthropology, but also for the sort of lack of privileging that mapping exercises like these can inspire–these maps get their meaning from the intentions of the people drawing them as much if not more than from the interpretations we researchers later layer onto them.

Anthropologists are not always fantastic at not-privileging their interpretations of meaning, and I’ve been helped in this regard by the neo-Boasian appeal of Bunzl. I frequently talk about being a sort of “native ethnographer,” as an academic studying academia, but Bunzl’s critique of the necessity of outsider status to anthropology is making me rethink that. Our position as “outside” or “inside” is not as important as paying attention to what is present, and describing it as thoroughly and thoughtfully as possible. It is not that interpretation is impossible, but that what we think things mean can and should be informed by a variety of perspectives, including that of the people among whom we are doing our work.

What is important about the maps, and I think about research generally, is the process, the questions and the discussions they inspire, not the end result. Thoughts about meaning should emerge from the discussion, from the process, and should never be framed as The Answer.

References:

Bunzl, Matti (2004), Boas, Foucault, and the “Native Anthropologist”: Notes toward a Neo-Boasian Anthropology. American Anthropologist, 106: 435–442.

Images:

Google Maps, Google Earth screen shots

Tube map is a crop of: http://www.tfl.gov.uk/cdn/static/cms/documents/large-print-tube-map.pdf

.jpg)

.jpg)